April 18, 2017

Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org

One Liberty Place, viewed from Veterans Stadium in December 1987, was the first building to rise higher than the William Penn statue atop City Hall, visible at far right. Within five years of its completion, Philadelphia boasted seven skyscrapers taller than City Hall.

The steps leading to the Philadelphia Museum of Art have long marked the most iconic location to gaze at the city's skyline.

Naturally, some 1,500 people assembled there on a crisp December night three decades ago to celebrate the topping off of One Liberty Place, which glistened amidst blue laser beams that flashed across the sky.

In the distance, the William Penn statue atop City Hall's 548-foot tower stood surrounded by scaffolding and pipes, essentially uninvited to the party.

The ascension of One Liberty Place — the first skyscraper to rise above Billy Penn's hat — had sparked a contentious public debate about the city's skyline, and by extension, its identity. But the building's approval precipitated a flurry of Center City high rises that quickly transformed a nondescript skyline into one that architecture critic Paul Goldberger called "one of the most appealing" in America.

"I think that breaking through that artificial ceiling was a way of people saying that the sky is the limit for this city," former Mayor W. Wilson Goode said of the momentous decision. "Let's go and not be held back by any type of artificial barrier."

Now, a second high rise boom is again altering the skyline, with the Comcast Technology Center set to become the city's tallest building and a spate of shorter towers rising along the western edge of the Schuylkill River.

But the current changes are less dramatic and have resulted in far less civic angst than those witnessed in the 1980s. After all, an entire generation has known nothing but a cityscape defined by glistening glass towers.

But in 1984, the proposal of two skyscrapers that would tower above City Hall — the historical center of the city — sent Philadelphia into a tizzy.

The tower of One Liberty Place soars behind City Hall.

City Hall had served as Philadelphia's visual focal point since its completion in 1901, when it ranked among the tallest buildings in the world.

While other American cities watched their skylines soar to new heights, Philadelphia maintained a more measured approach. A number of mostly unremarkable office buildings arose in the vicinity of City Hall, but Penn's perch atop the city remained protected by a gentleman's agreement and, to some extent, sheer economics.

To many, the statute of Pennsylvania's founder remained sacrosanct. Others cherished the minimalist cityscape as uniquely Philadelphian, a throwback to an earlier time.

So when Willard Rouse III and his development company, Rouse and Associates, rolled out plans in April 1984 to build the skycrapers that became One and Two Liberty Place, he was met with considerable opposition.

"The resistance we ran into was pretty immediate and pretty staunch when we proposed the taller buildings, because of the so-called gentlemen's agreement that nobody build taller than William Penn's hat," said Joe Denny, then the president of Rouse and Associates. "You can research that gentlemen's agreement and you can come to all kinds of conclusions on where it came from and who gave it the name. But it did lead to a fair amount of resistance."

Willard Rouse III: the man who built One Liberty Place

Bacon decried the proposed skyscrapers, claiming their density would destroy the downtown atmosphere. He voiced his opposition in the The Inquirer, whose editorial board echoed his criticism.

"It's a total disaster," Bacon told the New York Times in 1985. "It absolutely decimates the scale of Center City, and once it's been done there's no stopping it."

A poll published by the Philadelphia Daily News found city residents opposed breaking the height limit by a 2-to-1 margin. And Goode, who had pledged his support, found his mailbox flooded with opposition letters.

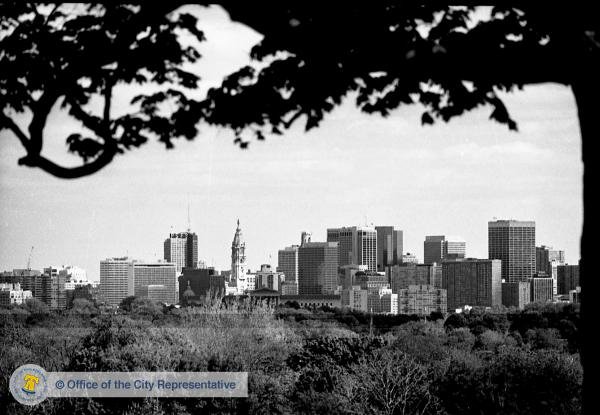

The Philadelphia skyline, as viewed from Belmont Plateau in 1983, was capped by the William Penn statue atop City Hall.

"My mail ran 1,000-to-1 against it," Goode said. "Someone organized a campaign that basically had people sending in postcards that essentially said 'No' on the height limit removal."

Rouse and Denny drew significant criticism as they made their way to numerous public meetings. When Rouse unveiled his plans to the city's planning commission, he displayed two cardboard models. The taller of the two models toppled as he spoke, eliciting scattered applause among the 300 people in attendance.

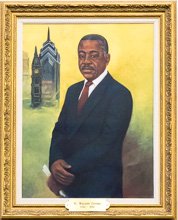

The official portrait of former Philadelphia Mayor W. Wilson Goode that hangs at City Hall, features One Liberty Place in the background.

Legally, the gentlemen's agreement held no merit. Rouse needed no variance to build higher than City Hall. But he needed public support — and he found it in key places.

Goode had vowed his support before Rouse made his proposal public. Councilman John Street, whose district included the proposed sites, offered his, too. Together, they worked to win the backing of City Council.

"If you don't take risks, then things don't move," Goode said. "It was my absolute view, at that time, that if we did one or did two, that more would come and that there would be a major kind of rebirth of Center City from the days of the '50s and '60s."

Goode took the planning commission to City Hall's observation deck, where it became clear that shorter buildings already obstructed sight paths to the northeast and southwest. Soon, most members of the Planning Commission were on board, too.

Philadelphia's skyline was about to undergo a dramatic change.

For many years, one of the most prominent buildings in the Philadelphia skyline has been One Liberty Place, this view was taken from Two Liberty Place.

The man tasked with designing the controversial skyscrapers was a German-born architect at the forefront of the postmodern movement in Chicago.

Helmut Jahn had emigrated to the United States to further his architectural studies in the 1960s. Two decades later, he had gained acclaim for designing the State of Illinois Center in Chicago, even landing on the cover of GQ in 1985.

Yet, Jahn became connected to Rouse and Associates in an unusual fashion — through an architectural contest. His firm beat out three others competing to design Rouse's Center City development, which initially called for three smaller office towers.

When the project changed to include a skyscraper that would surpass City Hall, Rouse told Jahn the building "better be done good."

Jahn understood. Not only would One Liberty Place rise above City Hall, but, at 945 feet, it would dominate the skyline.

"When a building replaces a public building ... it has a responsibility to have a content, to have an expression which justifies that it is so tall," Jahn said. "So many buildings do that — the Washington Monument, the Eiffel Tower in Paris. Just built for an exhibition — now, it's the most memorable thing you identify with in Paris."

For influence, Jahn turned to New York City and its Chrysler Building, an Art-Deco classic beloved for its terraced crown.

Jahn incorporated similar setbacks into the top of One Liberty Place and mimicked the shapes along its core. But unlike the stone and steel facade of the Chrysler Building, Jahn cast his building in reflective blue glass and granite.

His designs for Two Liberty Place, which opened in 1990 and stands 846 feet tall, initially included a similar top. But it was redesigned to accommodate the needs of its tenant, Cigna.

Designing a skyscraper with an interesting — yet functional — top is a difficult endeavor, Jahn said. The top floors of One Liberty Place, which now boasts an observation deck, are filled with interesting, but usable spaces.

"Buildings aren't just monuments," Jahn said. "They have to be functional. This is something we're very keen about — if it works first and if it's constructed the right way."

As his career evolved, Jahn shifted away from the postmodern designs that comprised his earlier work, like Liberty Place and the Messeturm in Frankfurt, Germany. But he came to reappreciate the buildings after viewing a photography exhibit that portrayed some of his earlier work.

Thirty years later, Jahn sees One Liberty Place as a skyscraper that has aged well, both structurally and visually. It may no longer be the tallest tower in Philadelphia (that would be the Comcast Center), but it remains a defining one, he said.

"It's not how new and how interesting a building is when it's finished and it gets a lot of attention," Jahn said. "It's what you think of a building after the test of time. This is why I'm glad to talk to you — this tells me that Liberty Place is still a building you look at. The good buildings get better in time. The bad buildings you forget."

Philadelphia's skyline in October 1990, as viewed from the South Street bridge.

One Liberty Place officially opened in August 1987.

Within five years, Philadelphia boasted seven buildings taller than City Hall, all clustered within the city's business district. The new skyline, which now included the BNY Mellon Center and its pyramid top, received rave reviews.

Approaching Philadelphia "became exciting for the first time in recent memory," New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in 1990. Though he found some buildings underwhelming, collectively they gave Philadelphia "one of the most appealing skylines of any major American city."

"And by happy circumstance the buildings are sufficiently well spaced to permit them to be seen from the street as well as from afar; they do not crowd each other so tightly that they blur into a granite and glass mush, as happens in much of midtown Manhattan," Goldberger wrote. "Yet neither are the buildings of Philadelphia so distant as to miss the chance to create a powerful image for downtown — or, as the locals call it, center city."

The residential fury — so strong at the onset — had subsided, too.

Wilson Goode no longer was receiving angry letters. Developer Joe Denny was hearing nothing but praise. And The Inquirer's editorial board — once scathing in its criticism — had come around, too.

"The good buildings get better in time. The bad buildings you forget." – Architect Helmut Jahn, designer of One Liberty Place

"All kinds of controversial projects, once they get built, are far less controversial," said Alan Greenberger, a former chairman of the city's planning commission. "People frequently have a difficult time truly envisioning what these places are going to feel like."

A longtime architect and former deputy mayor, Greenberger's employer at the time, Mitchell/Giurgola Architects, was among the four firms that submitted designs for the project that evolved into One Liberty Place.

Greenberger remained sympathetic to the people who wanted to respect the height limit, believing their arguments held some merit. After all, Washington restricts buildings from blocking views of the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol.

But Philadelphia is not Washington. And Greenberger is confident the city made the correct call.

"Those are pretty foundational buildings and monuments to the history of the United States," Greenberger said. "City Hall has that importance to the city of Philadelphia. But does it have that much importance that one should have respected that height limit in perpetuity?"

Greenberger says no.

If nothing else, One Liberty Place ushered an array of skyscrapers with interesting tops into the cityscape.

The BNY Mellon Center added an illuminated pyramid to Philadelphia nights. One and Two Commerce Center are each topped by a pair of stone diamonds. The blue reflective glass of the G. Fred DiBona Building extends into a glass gable.

"Prior to that time, there wasn't anything that had more than a flat top," said Robert Shuman, a principal architect at MGA Partners and a professor at Temple University. "These are the first things that raised heads above the skyline. ... Not only did they break the height barrier, but they kind of celebrated it."

The Comcast Technology Center, right, will surpass the Comcast Center as the tallest building in Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia skyline continues to reach both upward and outward.

The Comcast Technology Center will ascend to 1,121 feet, surpassing the Comcast Center as the tallest in the city. When the 60-story tower opens next year, it will include a Four Seasons Hotel, retail outlets and a restaurant on its top floor.

The skyscraper, rising rapidly, already blocks the view of One Liberty Place from the steps of the art museum, the very place where the city's bigwigs celebrated the evolving skyline three decades ago.

"Everybody throws around that term 'visionary,' but Bill [Rouse] actually was one. He was literally obsessed with the idea of making Philadelphia a better city." – Joe Denny, president of Rouse and Associates when Liberty Place was built

Today, 10 skyscrapers have risen above the heights of City Hall, including the FMC Tower, the tallest of several skyscrapers that have risen along the western edge of the Schuylkill River.

Though they are mostly smaller than their brethren in the financial district, their LED lights quickly draw attention at night.

"There's sort of a second center that is having a conversation with (the skyscrapers) across the river," Shuman said. "You get the feeling that it's spreading. At the time Liberty Place was built, you didn't get a sense of that economic march."

Though Willard Rouse died of lung cancer in 2003, his influence on the skyline is still being felt. Both the Comcast Technology Center and the Comcast Center, completed in 2008, were developed by Liberty Property Trust, the publicly-traded company that Rouse and Associates birthed.

According to Denny, who served as president of both companies, Rouse did not set out to shatter the so-called height limit.

But the late developer had the temerity, and the financing, to do it.

"Everybody throws around that term 'visionary,' but Bill actually was one," Denny said. "He was literally obsessed with the idea of making Philadelphia a better city. He was like a man on a mission from God to make the city a better place."

The Philadelphia skyline as seen from the 'Dalian on the Park' building above Whole Foods Market near the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

In the early 1980s, that meant better connecting the prime — but sleepy — office space on Market Street to the more energetic — but volatile — retail corridor along Chestnut Street.

Rouse and Associates began purchasing parcels along the block that now houses Liberty Place. But another developer, the Oliver Tyrone Corp., also was gobbling up the land. Neither had enough space to realize their visions.

The two developers agreed to participate in a winner-take-all auction for the land in 1983. Rouse won, submitting a bid that never was disclosed.

Rouse initially considered constructing a trio of high-rise office buildings — the tallest, at 38 stories, fell below City Hall's height limit. But the plans proved too dense to incorporate the public space necessary to connect Market and Chestnut streets.

"In one of these meetings — and I don't know who to give the final credit to — somebody took one of these (three model) buildings, cut it in half and put it on top of the other building and moved them apart," Denny said. "If you had two buildings instead of three buildings, then you have all kinds of better things you can do at the ground level."

Suddenly, the project included two skyscrapers, a shopping mall and a hotel. And, of course, a lot more controversy.

"Every city has gone through those moments," Greenberger said. "We just happened to have one in a city where the top of that statue was thought to be sacrosanct, and mistakenly thought to be law."

G. Widman /Visit Philadelphia™

G. Widman /Visit Philadelphia™ Credit/Liberty Property Trust

Credit/Liberty Property Trust Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice