September 28, 2018

Source/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Source/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

A girl stands next to her sister, who is lying in bed fighting the influenza virus, in November 1918. The young girl became so worried that she telephoned the Red Cross Home Service, which came to help care for the woman, whose husband was on the battlefield in France.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” Charles Dickens wrote in 1859.

Nearly 60 years later it was an apt description of life in Philadelphia.

World War I was winding down, victory in sight. The city had proudly and vigorously raised millions of dollars to support the local soldiers on the battlefield. The patriotism and excitement was palpable: the boys would be coming home soon.

But in late summer 1918, the city was in “the grippe” of a second wave of a Spanish influenza epidemic sweeping the United States. The city was quickly plunged into misery. Illness and death and decay was everywhere. Dread and despair tormented the living. Unspeakable indignities visited the dead and alive.

For two weeks in September and October, from the start of the epidemic through some of its darkest days, the city’s newspapers chronicled the misery in the streets of Philadelphia. But they also shared tales of heroism, hope, frustration and evil.

Here’s how the epidemic played out – day by day – for days immediately after the Liberty Loan Parade that many experts say led to the explosion of influenza in Philadelphia. They were some of the darkest days this city and surrounding towns have ever seen.

It was to be a show of support in the city’s effort to raise funds for World War I.

Two hundred thousand people turned out for the Fourth Liberty Loan parade down Broad Street in Philadelphia to watch songs and speeches, fife-and-drums, bayonet drills, four horse-drawn, eight-inch howitzers and planes flying overhead. Veterans of the war – “the gold chevrons of their service and their sacrificing leaming in the sun,” the Inquirer sung – rode through the crowd, which removed their hats in salute.

At 12th and Market, Joseph and M.E. Snellenburg placed the "world's greatest Liberty Loan sign" on their department store. Two stories tall and 200 feet long, it took weeks to create, and throngs of people gathered for the dedication.

But even as a million-dollar appropriation was rushed through Congress to fight Spanish influenza – it was roiling in Boston – news of imminent victory in Europe dominated the Philadelphia papers.

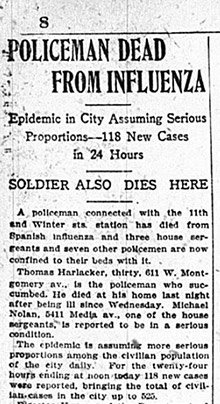

A story about the worsening outbreak ran on page 8 of The Evening Bulletin:

“POLICEMAN DEAD FROM INFLUENZA: Epidemic in City Assuming Serious Proportions – 118 New Cases in 24 Hours,” the headline read.

In fact, 70 people were already dead before the big parade stepped off, and scores of new cases were being reported daily.

News story on page 8 of The Evening Bulletin's September 28, 1918 edition. News coverage of the influenza epidemic was overshadow by war news from overseas.

The epidemic – worsening for more than two weeks after beginning almost unnoticed – had grown serious, declared Dr. Wilmer Krusen, director of the Department of Health, saying Philadelphians had to help curb its spread by avoiding careless behavior. And yet Krusen, yielding to political pressure, allowed the Liberty Loan Parade to proceed. Tens upon tens of thousands sharing germs on a sunny day.

It proved to be a questionable – and perhaps deadly – decision.

News of the Liberty Loan campaign dominated the Sunday Inquirer, which reported that 10,000 promotional circulars were dropped on the city.

In Camden, the parents of George Davis received word that their son had died on the battlefield in France. But people were dying right in Camden of influenza, or "the grippe," as it was known.

Two were dead of flu at the city’s Homeopathic Hospital, where there were six other cases, including two nurses. At Cooper Hospital, Alvina Speilmeyer, 32, died one day after her 11-year-old son. Two other sons fought the disease at Municipal Hospital.

Camden had thousands of flu cases, with hundreds in nearby Gloucester City. Officials closed public schools in Camden and Gloucester counties.

Over the weekend, 39 new cases were reported to the Bureau of Vital Statistics in Philadelphia.

It was the calm before a deadly storm.

Some of Pershing's wounded soldiers visit Philadelphia in October 1918 to boost the Fourth Liberty Loan drive. The men served under General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing, who in 1917-18 was the commander of the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front in World War I.

Mild weather.

That’s what physicians in Philadelphia were hoping would KO the epidemic. It was under control, they said, a few consecutive days of warm temperatures would halt it altogether.

Commander R.W. Plummer, of the Fourth Naval Reserve District, believed the worst of the had passed. Still, the number of deaths was jumping as more virulent forms of the disease appeared.

Among the dead was Miss Maude Sproule, a solo vocalist with the Philadelphia Orchestra said to possess a voice of rare quality.

More than 25 percent of the 300 soldiers stationed at the Frankford Arsenal were hospitalized with the disease, which also raged at nearby Camp Dix (62 deaths) and in Massachusetts (85,000 cases).

“The hospitals of Philadelphia are crowded to the doors,” Dr. Wilmer Krusen, the city’s health director, told an emergency conference at City Hall.

To make matters worse, doctors and nurses at many hospitals were coming down with the flu. Those still on their feet didn’t have many tools. There was no flu vaccine to prevent infection, no antiviral drugs to treat illness and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections, like pneumonia. The invention of the mechanical ventilator, or “iron lung,” was 10 years away..

The Red Cross asked every woman with nursing training to sign up for immediate service.

"In some families there are none left to take care of burying their dead and others are unable to bury them or cannot get undertakers.”

In Germantown, 1,100 students at Immaculate Conception Parochial School were told to stay home: 9 of the 20 nuns who teach at the school were stricken.

The day brought 635 new civilian cases in Philadelphia.

A Bulletin editorial cautioned that the crisis had not passed: “...There has been considerable apprehension excited in this city over the possibility that there may be an outbreak here like the one in Boston … but victims in the mortality lists are numerous enough to show that it may be dangerous, and that it is by no means to be trifled with.”

Edward F. Bennis Jr., 24, of Germantown, died at the naval barracks in Cape May after a week-long illness that became pneumonia. His mother and father were at bedside when he passed – wearing masks.

The number of new cases was rising everywhere: 500 in Bristol, 100 in Coatesville, 100 in Norristown, 2,400 in Wilmington. The news was no different across the river. In Gloucester City, health officials closed schools, churches and moving picture houses. Public gatherings were banned.

The newspapers chronicled the suffering and sadness during the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic.

Dr. J.K. Bennett, a city physician and medical inspector in Gloucester City, was in serious condition from the flu and unable to attend the local Board of Health meeting. ("Policeman Harvey toured the city at 4 o'clock this morning trying to find a doctor to go to Bennett's home, but could not locate one,” the Inquirer reported.)

In Camden, hundreds of new cases developed. The city’s circuit and criminal courts were closed.

There were selfless acts of charity.

Mrs. Fred Maule was in Philadelphia Hospital with influenza, her three small children malnourished. A day earlier, flu took her husband in their ramshackle home at the rear of Hamilton Street, the Evening Public Ledger reported. A few hours later, she gave birth to another child at home, who died within minutes.

The Maules were the only white family in an impoverished neighborhood. But when the widow took ill, two or three African-American women took turns nursing her while other neighbors cared for the starving children, ensuring they were not forgotten at meal time.

When Philadelphia Mayor Thomas B. Smith committed the city's $100,000 emergency fund to fight influenza, it was perhaps the first sign that officials were taking the public health threat seriously.

Camden and Collingswood closed churches, theaters and places of amusement. Six Delaware County towns, including Media and Upper Darby, followed suit. In Philadelphia, there were 658 new cases – with 143 deaths, the most yet reported. There were 40,000-50,000 total cases in the city, it was estimated.

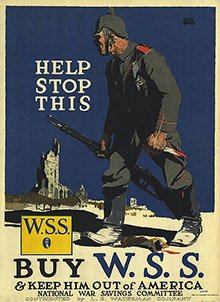

This promotional item tells Americans to buy war savings bonds in order to keep the Nazis out of America. The illustration shows a very large figure of a uniformed man holding a bloody knife and rifle as he steps over a dead body.

About 4,000 pupils were ill citywide, and state Sen. Edwin H. Vare said conditions in South Philadelphia were the worst he could remember. People were panicked, doctors overworked and pharmacies short on drugs.

Samuel Rosins, a druggist at Fourth and Dickinson, collapsed at work, and two of his clerks took ill soon afterward. More than a thousand students at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy were recruited to help dispense medicine around the city.

In Gloucester City, influenza was sweeping through town. Practically every doctor was said to be suffering from the disease. One undertaker had nine funerals in three days.

And on East Lehigh Avenue in Kensington, a 15-month-old girl was orphaned when her mother succumbed to pneumonia contracted while attending her husband, who died a day earlier.

Many influenza patients were transported to hospitals by horse-drawn ambulance in 1918.

When the stats increased again, Philadelphia churches, schools and theaters were closed – immediately. New daily cases numbered 636 in Philadelphia, with 139 deaths.

"I never heard of such a thing," the Right Rev. Monsignor Edmond J. Fitzmaurice, chancellor and vicar-general of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, told The Evening Bulletin, "but the Catholic church, as usual, will obey the law."

Another church leader, Presbyterian Rev. Dr. William H. Roberts, lamented that the Board of Health was favoring saloons – which were not included in the order – over churches..

By the end of the day, state health authorities closed saloons, too, plus dance halls, poolrooms and boxing arenas. There were additional drastic measures. No visiting of the sick, except in desperate cases. Only private funerals, attended by adults, not in a church or chapel.

“When you're fighting the Huns, keep on fighting, but in fighting influenza it is best to surrender at once." – Dr. Wilmer Krusen, Philadelphia health director

A big Liberty Crusade parade planned for the following week at the Academy of Music was called off. Former President William Howard Taft was disinvited from a Liberty Loan mass meeting.

Four police dispensaries in South Philadelphia, including one at 2nd and Christian, now were receiving patients. Physicals for draft registrants in were halted and Philadelphia Rapid Transit was disinfecting trolley cars.

Things were so bleak for Edward Dessin, 45, of West Somerset Street, whose wife and two little children were all in different hospitals, that he attempted to hang himself at his home, police reported.

In Gloucester City, four physicians – from Philadelphia, Camden, Atlantic City and Wildwood – responded to a call for help, and were immediately provided automobiles and drivers to expedite their work. Twenty women – working nurses before marriage – cared for hundreds of people in their homes. In one home, 11 children were found lying ill on the floor.

Dr. Fred C. Robertson, sent there by the state Board of Health to survey the situation, instead found himself attending to many patients.

In Burlington City, residents with sick patients in their homes put cards on their front doors to tell doctors, druggists and nurses to enter – without ringing.

And Bell Telephone Company pleaded for fewer calls. With so many operators sick in bed, the public was urged to leave the phone in its cradle – to keep the wires clear for emergency medical calls.

Nearly a week after the Liberty Loan parade, a new health problem was mounting: contagious corpses.

In homes and on porches, the bodies of the dead decayed, threatening to spread the disease. A shortage of caskets delayed funerals for hundreds of victims, and undertakers were overworked; one in Camden said he had 21 cases in just several hours.

Dr. Wilmer Krusen was the city's top health official during the 1918 epidemic.

With mandated reporting by physicians, the number of new cases grew to 788. The state was now reporting 52,000 active cases.

The E.G. Budd Manufacturing Co. at 25th and Hunting Park, builder of the first all-steel automobile bodies, hired a nurse to visit the homes of afflicted workers. At the plant, employees were consuming gallons of Dobell's solution.

Krusen said he expected the wave of “epidemic influenza” to run its course by October 24. "The name Spanish is not the correct name," he told reporters. "The influenza is no more Spanish than American, or Dutch or Italian or French.”

He advised adults coming down with flu symptoms to wave the white flag: “When you're fighting the Huns, keep on fighting, but in fighting influenza it is best to surrender at once. Go to bed, have a doctor summoned, and stay in bed until you are well."

It was, at that point, the deadliest week in Philadelphia history, with nearly 700 lives lost to influenza and pneumonia, including 254 deaths in the last day alone. There were 1,480 new cases for the day: north of Market street, 677 new cases; south of Market street, 381; West Philadelphia, 341; and 81 in Germantown and Oak Lane.

Yet, one city physician declared that the widespread alarm was needless. Dr. John W. Croskey, president of the West Philadelphia Medical Association, and other doctors began an "anti-scare" campaign to offset the panic, saying the actual influenza mortality rate was only about one-half of one percent, the Evening Public Ledger reported.

"Auto-suggestion (or self-suggestion) has much to do with the present state of mind of the people of Philadelphia," he said.

If gauze masks were worn in public, commented one military official, the disease would disappear in a few days. A city health official blamed careless coughing and sneezing.

In Camden and Gloucester City, officials shuttered saloons at least partly out of concern that keeping them open would represent a dangerous invitation to thousands of people from “dry-bone” Philadelphia to find drink in their towns. In Southwest Philadelphia, a frenzied crowd smashed the display window and grabbed bottles at a liquor store at 63rd and Woodland.

The University of Pennsylvania allowed medical school students to assist overworked physicians, who were flying green flags on their cars to gain the right of way over regular traffic.

John Morris, 29, of West Seymour Street, drove an ambulance on influenza cases at St. Timothy Hospital nearly to the hour of his death. Ill with the disease for two or three days, he remained on the job amid the dearth of drivers. When doctors finally ordered him to bed, he died within hours.

Charles Pitcher Hubbard, 26, a corporal from Wyncote, Montgomery County, died of influenza at Camp Humphries, Va. and was buried at Arlington. He had come 5,000 miles from Japan to enlist in the military.

In Gloucester City, Mrs. Charles Schaeffer died of influenza a week after her 13-year-old son was struck and killed by a train.

With no church services permitted on Sunday, pastors urged their members to kneel in prayer at 11 a.m. for the end of the epidemic, quick recovery of the sick and an early ending to the war.

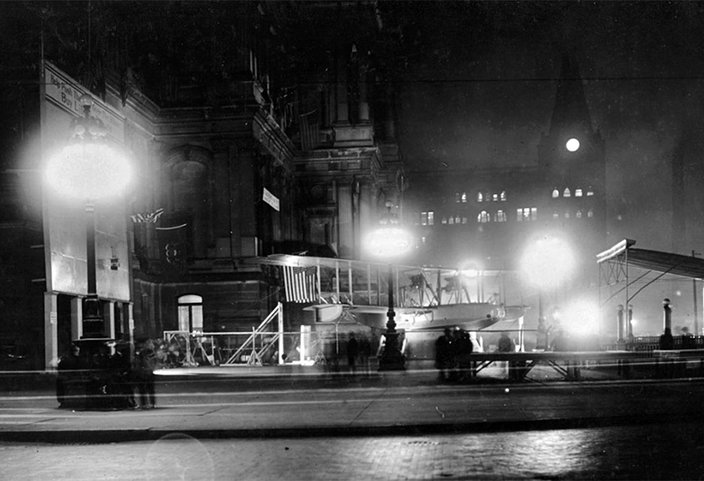

A Curtiss F5L seaplane sits on exhibit outside Philadelphia City Hall at night on October 17, 1918. A Liberty Bond billboard stands at left. The Naval Aircraft Factory at the Navy Yard built 137 of the patrol flying boats. During the influenza epidemic, passersby who stopped to view the exhibit, or to study The Bulletin's war map nearby, were told by a guard to “keep moving.” Health officials did not want people to congregate for long for fear of spreading the disease.

Morning dawned on “Churchless Sunday.”

For the first time in the history of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, Catholic churches were closed as part of the order prohibiting congregation at houses of worship.

No services were held at the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Germantown, where the Rev. J.M. Higgins, otherwise had a message for worshippers: the sins of the world had led to the epidemic and World War I.

The epidemic continued to spread, with more than 5,500 cases in the past 48 hours. The Bureau of Vital Statistics was open just two hours, but 115 deaths were reported.

In North Philadelphia, a brother’s dedication to his flu-wracked 13-year-old sister eventually took his life, too. When Agnes Foggarty fell ill early last week, her brother John helped nurse her, failing to leave her side until his own collapse. He died a few hours after her and they were buried together.

Meanwhile, the Liberty Loan campaign plowed on, with a demand for Philadelphia to triple its subscription. The weekly slogan was “Wake up Philadelphia!”

With the Philadelphia morgue practically full – 40 bodies – the city health director was asked to halt the delivery of more corpses by police, or find a larger repository. Cemeteries across the area said they were struggling to bury the dead, and still unable to get sufficient help to speed funerals.

The influenza outbreak was "nearing its crest," Krusen told reporters. With 5,561 new cases over the weekend, officials estimated 175,000 people in the city were stricken. The number of deaths hit 629 over the past two days.

Bodies are embalmed at the Philadelphia morgue during the influenza epidemic of 1918 in this photo from a newspaper clipping. During the height of the outbreak, bodies were stacked three and deep – several hundred corpses despite a capacity of 36 – and covered only by dirty and blood-stained sheets. Most were unembalmed and not stored on ice.

Two other emergency hospitals opened: the main building of the Medico-Chirurgical Hospital at 18th and Cherry, and the Catholic Philopatrian Club in the 1400 block of Arch Street, where parochial school nurses and attendance staffs volunteered.

Krusen continued to prescribe advice to the public on flu prevention: "Keep warm. Keep out of crowds. Keep the bowels open. Eat and sleep well. Breathe fresh air."

In an effort to meet the need for flu drugs, wholesale drug laboratories were working nights and Sundays. A Smith, Kline and French official said the demand was about 10 times greater than normal. Furthermore, the companies’ delivery systems were overburdened and slow.

"We have the influenza epidemic situation under strong control," Krusen declared, noting fewer calls for doctors and hospital transports. New cases totaled 3,831, about the same as the previous day, with more than half of those cases in North Philadelphia.

With druggists running out of liquor supplies, saloons were permitted to fill prescriptions. Ninety percent of the city’s doctors were prescribing whisky as part of flu treatment, according to the Liquor Dealers' Association.

Streets were flushed and more people were donning anti-epidemic masks, some of which consisted of a semicircular piece of wire gauze, which fit over the mouth and nose. A removable piece of medicated gauze – to be replaced every day – fit over the wire. The used gauze was burned.

In Minersville, a town in Pennsylvania’s Coal Country, where 20 percent of the population was afflicted, hospital tents were erected in the streets. Six children in one family laid dead in their home at one time.

With nearly all of the hospital beds in Philadelphia occupied by influenza patients, the Philopatrian Club home at 1411-13 Arch Street was transformed almost overnight into a fully-equipped hospital. It was turned over to the city on October 7, 1918. There were a number of similar “emergency hospitals” opened around the city to help meet the crush of epidemic victims.

Nearly a month after the start of the flu epidemic, one thing was clear: people were continuing to get sick and die.

The epidemic, according to Bureau of Health statistics, was officially the worst in the city’s history, both in terms of cases and fatalities. During the epidemic of 1880, the death rate was 20.45 per thousand; in the last week, the death rate reached 35 per thousand.

The misery index was off the charts, too.

The bodies of two influenza victims lie on the 1500 block of Hanson Street in Southwest Philadelphia for several hours without attention from an undertaker.

The epidemic left two more orphans – a four-year-old and a two-month-old – after their parents, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Chappell of Haines Street in Germantown, died two days apart. A double-funeral was planned.

One undertaker allegedly said he would bury a dead girl in a pine box for $100 – if the child’s father would dig the grave.

James McKeffry, 39, who lived at 3836 N. 15th St., was in bed with the grippe when he jumped up and leaped out a second-story window, suffering a compound fracture of the right leg and possible internal injuries.

Another man, 27, who had just recovered from influenza, was near his Manayunk home when he was struck by a train and thrown 15 feet. His wife, also sick in bed, heard about the accident, jumped up and and ran to the scene in time to see her husband taken away. She collapsed.

Richard Brady, a coal driver from East Haines Street still recovering from flu, had another brush with death. He was filling his wagon when the load spilled, burying him under 50 tons of coal and sweeping him into the company's bins, 15 feet down. It took a half hour for 20 men to dig him out. He regained consciousness en route to the hospital, and was sent home in a couple of minutes, with nary a scratch.

Dozens of St. Charles Seminary students dug graves at Holy Cross, Holy Sepulchre and New Cathedral cemeteries. And 1,000 sisters of the Order of St. Joseph were given special dispensation to work in private homes to care for the sick.

Camp Dix in Burlington County was hit hard by influenza and pneumonia. Living in close quarters, the disease moved quickly among servicemen and spread to civilians.

Finally, the epidemic seemed be waning.

The 3,385 new cases was the first decline since onset of the disease. A similar trend was reported in Pennsylvania and in South Jersey. Still, the highest number of deaths so far – 514 – was recorded in Philadelphia and fatalities were expected to stay high for several more days.

The problem of interring all the bodies was worsening.

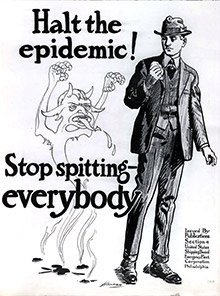

In this illustration from the Influenza epidemic of 1918, the “Spanish Flu,” in the form of a devil rising from pools of saliva on the ground, reaches out to attack a well-dressed man. “Stop spitting – everybody,” the text reads.

To speed the burials, a guard was provided to marshal grave-digging by prisoners from the House of Correction at the Woodlands Cemetery, where bodies were tagged they could reburied by relatives at a future date.

Lit Brothers donated two trucks to be used as ambulances in South Philadelphia. Patients were being treated at The Country Club at Collingswood.

Dr. Carl Stoepler, 36, of Girard Avenue, died at the Polyclinic Hospital. Just one of countless martyrs to duty, he attended the sick of the 29th ward for weeks, working 24 hours in recent days. He collapsed, died and left behind a wife and son.

Meanwhile, U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue told people to stop spitting and spreading the flu or be arrested. At the same time, a Jefferson Medical College epidemiologist recommended that the public refrain from kissing and that conductors halt the thumbing of trolley tickets.

A sign is posted inside a Philadelphia Rapid Transit vehicle during the influenza epidemic.

The city’s top law enforcement official blasted some downtown undertakers for taking advantage of desperate families. "We will do everything we can to help clean the city of such skunks," said the police superintendent, calling them "commercial ghouls."

An investigation showed several charging exorbitant rates to bury influenza victims. In some cases, burial was promised, if paid for in advance, and pine boxes went to the highest bidder regardless of who was first in line. Those undertakers identified as gouging profiteers would be prosecuted, driven out of business and jailed, police said.

One shady undertaker reportedly rejected a man at the standard $150 funeral charge, but offered – for $500 – to take a casket from another fellow "and give you a first class funeral right away." Another allegedly said he would bury a dead girl in a pine box for $100 – if the child’s father would dig the grave.

The lure of a mysterious cure attracted scores of people – on foot and in motor cars – to a home in Woodbury Heights, Gloucester County.

Bodies were left untouched for hours in some instances, where the undertaker would accompany a relative to an insurance office, then insist on the entire insurance to complete burial.

With 557 deaths for the previous day and a total of nearly 25,000 cases in the city since the start of the epidemic, unburied bodies were menacing public health. Undertakers were beleaguered. In one case, a body that sat unembalmed in a home for six days, badly decomposing. "In some families there are none left to take care of burying their dead and others are unable to bury them or cannot get undertakers,” said one health official, the Evening Bulletin reported.

Officials arranged to move bodies from homes to the morgue for embalming. They toured a brewer’s cold storage plant to assess its suitability as a temporary morgue. They leased a steam shovel to dig graves in a Potters' Field at 2nd and Luzerne.

At a home one block off Broad Street in South Philadelphia, two children suffering from influenza were carried from their beds when flames from an overturned gas range ignited the carpet in a downstairs room.

In Delaware, a casket was placed on a front porch before a funeral. While the undertaker was inside the house, a man came along and took the casket home to bury his wife in it.

Harry Jacoby, 36, who lived at Thompson's Hotel in Camden, jumped from a second-story window and fractured his skull, dying later at Cooper Hospital. A victim of influenza and pneumonia, he had been unable to get a physician, and it was thought he became deranged over his condition.

The lure of a mysterious cure attracted scores of people – on foot and in motor cars – to a home in Woodbury Heights, Gloucester County. Mrs. E.W. Egar claimed a remedy for influenza, the Evening Bulletin reported. She refused to identify the ingredients, but shared it free with everyone. So many automobiles arrived at her door, the roads near her home required repair.

For days and weeks after, people continued to die from the flu.

The sad and miserable stories continued:

• Thousands of dangerously ill men, women and children unable to receive proper care

• Hundreds of orphans and no place to send them

• The corporal's body that lie unburied for 12 days with no undertaker available

• The corpse of an influenza victim thrown from a hearse into the street in a collision at Ridge and Master

• The distraught Wallace Street father who went to City Hall for a burial certificate, his dead child under his arm

By November, however, as the country would celebrate a World War I victory, the sun shined again in Philadelphia. The city had lost nearly 13,000 of its people in just weeks, but life was slowly getting back to normal.

Source/The Evening Bulletin

Source/The Evening Bulletin Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center Source/Evening Public Ledger

Source/Evening Public Ledger Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center ./.

./. Naval History and Heritage Command/via Library of Congress

Naval History and Heritage Command/via Library of Congress Source/The Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Source/The Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Credit/phillyhistory.org

Credit/phillyhistory.org Credit: Harris & Ewing, photographer/via Library of Congress

Credit: Harris & Ewing, photographer/via Library of Congress Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Source/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center