February 08, 2024

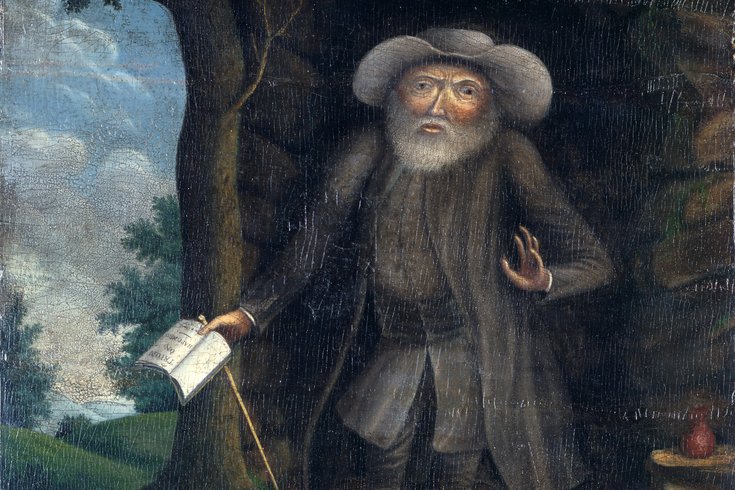

Public domain/William Williams

Public domain/William Williams

When Benjamin Lay moved to the Philadelphia area in the 1700s, he mounted stunt protests against slavery at Quaker meetinghouses and befriended Benjamin Franklin.

In colonial Philadelphia, it was hard to miss Benjamin Lay.

The abolitionist could often be found at Quaker meeting houses, admonishing members for their continued endorsement of slavery. His protests were confrontational, incorporating military dress, fake blood and at least one felony. He made his own clothes, wanting no part in human or animal suffering, and he had a distinctive appearance due to his dwarfism and kyphosis, conditions that lent him a 4-foot-7 frame and hunched back.

"Some will allege, and none can doubt, that he occasionally manifested symptoms of derangement," his biographer Roberts Vaux wrote in 1815. "Yet all must acknowledge that oppression will make a wise man mad."

Lay wasn't just a character shouting into the wind. He associated with powerful figures — including Benjamin Franklin, who published Lay's anti-slavery book — and his activism produced real change. Shortly before his death, the Quakers changed their position, voting to disown any member who owned or traded slaves. Yet despite Lay's achievements and eccentricities, he faded into relative obscurity after his death on Feb. 3, 1759. History buffs have been reexamining his story in recent years through viral TikToks and published texts — most notably, Marcus Rediker's biography "The Fearless Benjamin Lay" and co-authored graphic novel "Prophet Against Slavery" and play "The Return of Benjamin Lay," which premiered in London last year.

"He had a tremendous belief in what he was doing," Rediker, a professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, said. "In some ways, his success and his being a big part of this abolition movement, despite the fact that he didn't have the right kind of body, that I think is one of the reasons historians didn't pay much attention to him."

Lay lived in the Philadelphia area for nearly 30 years, but he was born in England and worked as a sailor until he married his wife Sarah, a fellow Quaker and little person, in 1710. The couple moved to Barbados a few years later, a major hub of the transatlantic slave trade where enslaved Africans outnumbered white settlers by nearly 10 to 1. Disturbed by what they saw, Lay and Sarah began inviting slaves into their home for food and friendship. Lay's very public screeds against slavery made him an enemy of the country's slaveholders, which eventually spurred him and Sarah to move to Philadelphia.

Lay's beliefs were shaped by Quaker tenets, which his parents had preached since childhood. As Rediker argues, his radicalism was in step with some of the earliest Quakers, who shouted down ministers in the Church of England in the 1640s and 1650s. The practice was so rampant that Oliver Cromwell issued a proclamation outlawing the heckling of ministers, which led to the imprisonment of hundreds of Quakers — including in Lay's native city of Colchester. These same Quakers also engaged in the kind of guerrilla stunts Lay soon staged in his new city.

As Vaux put it, Lay arrived in Philadelphia "rather like a comet, which threatens, in its irregular course, the destruction of the worlds near which it passes." He eventually took up residence in Abington, residing with Sarah in a cave they converted into a cottage. When the couple moved stateside, slave ownership was still common in Philadelphia, even among Quakers. Half of the members of the Philadelphia monthly meeting of Quakers owned slaves in 1732, the year that Lay arrived. William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania, had owned 12.

Lay could not reconcile what he saw as the foundational Quaker principle, treating others as you would want to be treated, with the institution of slavery. And so he began targeting Society of Friends gatherings to confront his peers over their hypocrisy, taking bold action to get their attention.

His most famous stunt occurred at the 1738 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Quakers, held in nearby Burlington, New Jersey. Lay walked into meetinghouse in an unusual costume that concealed something even stranger: Under his bulky coat was a military uniform, a sword and a hollowed-out book containing an animal bladder full of bright red pokeberry juice. After waiting his turn to speak, Lay declared slavery the greatest sin and warned that God would "shed the blood of those persons who enslave their fellow creatures." Throwing off his coat, he raised the book and pierced it with his sword, spattering fake blood on the slave-holding members in attendance.

"He didn't want people to be comfortable," Rediker said. "He used the phrase, he wanted to wake people up. They had fallen asleep, and were doing terrible things."

On another occasion, Lay stood outside a Quaker meetinghouse on a snowy day with his right leg and foot bare. When people stopped and expressed concern, he said they should worry about "the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half clad." He also briefly kidnapped the 6-year-old son of his slave-owning neighbor, beckoning the child to his home and keeping him out of view as his parents frantically searched. He eventually approached them and said, "Your child is safe in my house, and you may now conceive of the sorrow you inflict upon the parents of the negro girl you hold in slavery, for she was torn from them in avarice."

Lay published his views in a book often abbreviated to "All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates" — the actual title is much longer — with the help of his publisher friend Benjamin Franklin, an enslaver who eventually advocated for abolition. (Franklin's wife Deborah also commissioned a painting of Lay that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.) He continued spreading his message through essays and demonstrations in houses of worship, in some cases walking up to 30 miles to reach his destination. Lay refused to ride a horse due to his equally steadfast belief in animal rights, which inspired him to eat vegetarian and create his own cruelty-free clothes. Lay also dabbled in feminism, sometimes sitting in the women's gallery at Quaker meetings to protest the segregation of the sexes.

"The prejudice that he experienced as a little person sensitized him to the prejudice that other people experienced," Rediker said. "He had this hatred of discrimination and inequality."

Activism from Lay, another Quaker named Ralph Sandiford and the next generation of abolitionists within the Society of Friends helped push the Quakers' change of heart on slavery, a stance they adopted just one year before Lay's death. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Abington Friends Cemetery alongside Sarah, who had died in 1735. At the time of his passing, he had been disowned by his congregation for his direct actions against slave-holding Quakers.

The Quakers have come around on Lay in the centuries since his death. In 2018, the Abington congregation added a burial stone for Lay and Sarah and in 2022, the Friends House in London renamed its William Penn Room the Benjamin Lay Room. Some believe similar changes should be implemented in Philadelphia; a group called the Benjamin Lay Society has been petitioning since 2017 to replace the statue of William Penn atop City Hall with a monument to Lay.

Lay's likeness watching over Philly may be a longshot, but one thing is certain: The supposed heretic, now known as Benjamin Slay on social media, has been vindicated.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.