February 20, 2023

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

A postcard from the No Arena in Chinatown Solidarity's campaign is set against the neighborhood's landmark Friendship Gate. The artwork, by Quyen Truong, is just one example of recent protest art created and displayed in Chinatown to show many residents' opposition to the Philadelphia 76ers plans for a new stadium there.

Wander around Chinatown and you'll find a simple message plastered along storefronts and the sides of buildings: NO ARENA.

The posters are usually sparse, text-heavy and straight to the point. Since last year, residents and shop owners in Chinatown have made it clear they oppose the proposed Sixers arena at 10th and Market streets through these simple printouts, as well as with comments at community meetings and, in January, the formation of a 41-group coalition.

But as the protest movement has evolved, so has its messaging.

Last month, the No Arena in Chinatown Solidarity group conducted a postcard campaign, encouraging supporters to write messages to city councilmembers or Mayor Jim Kenney expressing their feelings about the arena. The front of these postcards features artwork borrowed from Asian Americans United's Mid-Autumn Festival 2022 poster, depicting smiling protestors holding picket signs under the neighborhood's famous 40-foot Friendship Gate. One sign reads, "VOTE VOTE VOTE," and another, "STOP AAPI HATE." But the one closest to the center carries that old refrain: "NO ARENA."

These 'no arena' posters plastered on a wall on Chinatown are among the ways residents in the neighborhood are publicly showing their opposition the 76ers stadium plans.

What began as a "fun poster for the warmest community," according to artist Quyen Truong's Instagram, has become a symbol of resistance. Two Chinatown restaurants, Bubblefish and Little Saigon Cafe, offer stacks of the postcards to customers via display stands. Outside of the neighborhood, the postcards are available at Pennsport sushi spot Ginza and Society Hill bar Tattooed Mom.

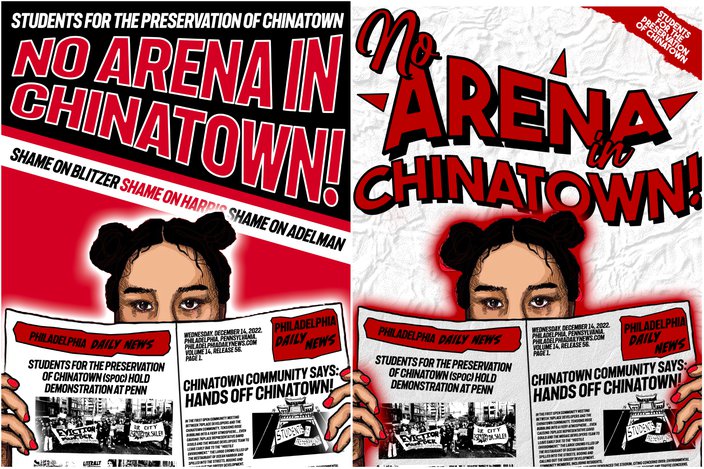

Some University of Pennsylvania students have also channeled artistry into protest through posters now featured at informational events about the 76ers arena plans at Chinatown's Asian Arts Initiative and Callowhill's Rail Park. Perhaps the most distinctive piece shows a woman peering over a newspaper with headlines about the arena protest. One version explicitly names (and shames) the arena's investors, Josh Harris, David Blitzer and David Adelman.

"I think a lot of the history of the world can be understood through activism art, and I think it's a really important tool especially for organizing," Alyssa Chandler, the Radnor native who drew the illustration, said. "I think that (there's) a moral obligation or responsibility for artists to use their skills for something good and especially to create something beautiful that can actually create change."

These are two variations on Alyssa Chandler and Kenny Chiu's poster, created for Students for the Preservation of Chinatown.

Chandler says that she finds inspiration in the art of the Black Panthers and 1960s student movements, but that the poster was a riff on an image from Green Patriot Posters, a collection of artwork that highlights environmental issues. Kenny Chiu, a fellow Penn student and organizer with the Students for the Preservation of Chinatown, approached her with the concept and helped with the layout and lettering.

Chiu, who was born and raised in South Philly, only lived in Chinatown briefly as a child, but considers it a haven for immigrant families like his.

"Chinatown was always just like the spot for all of our friends to gather to play basketball or to get food with families," he said. "My parents are immigrants from China and they settled here and they were able to find a community and sort of reconnect to the culture they lost when they had to move.

"Some of my family members, they've been able to get their first jobs in Chinatown, being non-English speakers. So, yeah, I think for my whole family, for myself, it's just an important place for us. It has everything. It's sort of a city within the city of Philadelphia."

Protestors have mostly relied on static images to promote the preservation of this "city within a city," but last weekend, they rolled cameras in Chinatown for the movement's first music video. Wielding a paper mache crane and drums, performers sang a parody of Miley Cyrus's "Wrecking Ball" with tweaks lyrics like, "You came in with a wrecking ball, completely disregarding us. But you don't get to make the calls. All your promises are empty, and we're ready."

By the shoot's end, the paper mache wrecking ball had been destroyed over the Vine Street Expressway.

While the video has not yet been released, it's the kind of piece made for and molded by social media, where protest messages and art can spread in minutes.

"I think a lot of people were made aware of No Arena in Chinatown because of the prints being reposted on Instagram," Chandler said. "It's kind of silly how Instagram and social media does have a role in activism nowadays, but I think that it's also really amazing how it's able to reach a greater audience."

The younger generations' fluency in Instagram has also allowed them to "find (their) niche," Chiu said, and build on the organizing efforts that previously defeated a proposed Phillies stadium in 2000 and a casino in 2009.

"We are here to not waste our ancestor's work in the previous developments," he said. "This is just another one of those fights."

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice Courtesy/Kenny Chiu

Courtesy/Kenny Chiu