May 04, 2016

Hayden Mitman/for PhillyVoice

Hayden Mitman/for PhillyVoice

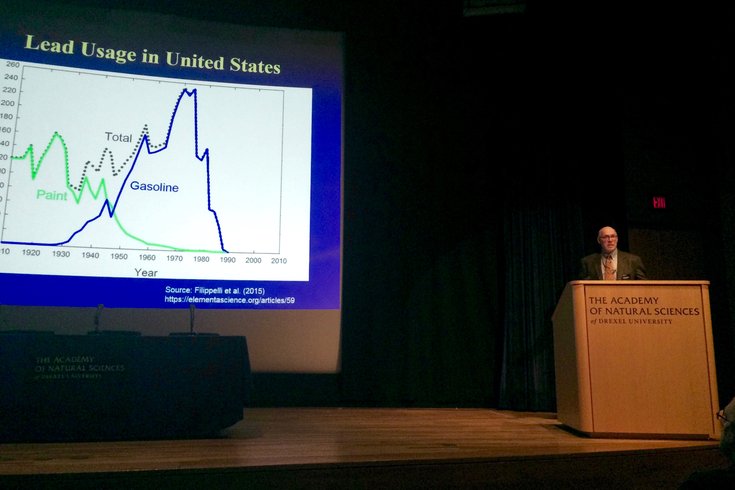

Moderator David Velinsky, vice president of science at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, discusses the historic uses of lead in society. During an event on Tuesday night called 'What's in Our Water,' experts detailed the dangers of lead poisoning and the work being done to keep it out of Philadelphia's water supply.

If you live in Philadelphia, your drinking water is lead-free.

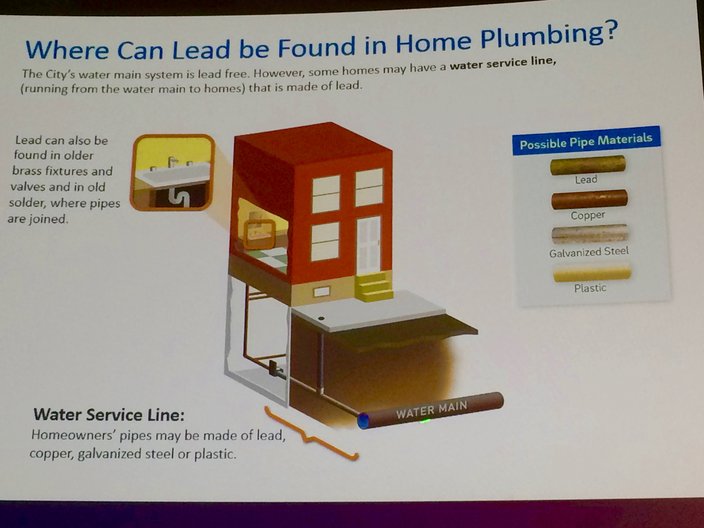

At least it is until it arrives at your home, according to city officials. Depending on the age of your home – and the pipes that carry water from the city main to your faucet – that water may or may not contain some amount of lead before it ends up in a glass or pot.

On Tuesday night, Debra McCarty, the city’s new commissioner of the Philadelphia Water Department outlined the efforts taken by the utility to ensure Philadelphia residents have the cleanest, clearest water possible. During a public forum titled “What’s in Our Water,” held at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, McCarty told residents how lead can get into their drinking water, and what can be done to prevent it.

“I like to tell people that our water quality is the best,” McCarty said. “I truly believe it.”

To kick off the meeting, McCarty wasted no time in addressing the water contamination tragedy in Flint, Michigan. Elevated lead levels were found in children’s blood after elected officials there changed the town's water source from a treatment plant in Detroit to the Flint River. The corrosive Flint River water caused lead from aging pipes to leach into the water supply creating a public health crisis.

That would never happen here, McCarty promised.

“We would never do what happened in Flint,” she said. "We do treat the water to make sure that lead doesn't leech out of the pipes, if there is lead... We do take this seriously."

Unlike Flint, Philadelphia has two great sources of water – the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers – and the water is treated with zinc orthophosphate to inhibit corrosion of city pipes.

Flint, she reminded the crowd, did not treat its water with a corrosion inhibitor.

In fact, McCarty said, PWD’s water distribution system is lead-free. But that guarantee ends at the curbline.

PWD estimates that about 10 percent of Philadelphia homes – typically built prior to 1950 – have water service lines constructed with lead. Those pipes runs from the water main outside to the water meter in the home.

This image shared Tuesday night shows the most likely places where homes - usually those built before the 1950s - could find lead piping. The image shows a lead service pipe connecting from the home to the water main in the street and notes that lead can potentially be found in old soldering and older fixtures.

PWD, McCarty said, has a constantly growing list of properties known to have lead service lines. Residents of city apartment buildings and high-rises likely wouldn't need to worry about having lead service pipes as the increase water volume would require larger pipes, McCarthy said, noting she seriously doubts that any pipes over an inch in diameter are constructed of lead.

Lead can also be found in old solder and old brass fixtures, but most likely homes would have copper or galvanized steel piping for water lines, she said.

If a home has lead pipes, it is the homeowner’s responsibility to have them replaced, but the utility company is working on several initiatives to speed the replacement process, McCarty said.

In addition to working with registered community organizations to disseminate information about lead piping, PWD is willing to replace lead service lines at homes in areas where water mains are being replaced, McCarty said. It also is working on creating a no-interest loan program for homeowners who need to pay to replace lead piping.

McCarthy said the PWD plans to announce more information on those loans by June.

“We are working on the logistics and details of the program,” she said.

PWD plans to perform water sampling next year for properties that might be at risk of having lead piping.

In 2014, the department attempted to survey about 8,000 properties constructed before 1950 and may have lead pipes, McCarty said. But less than 140 property owners responded.

With additional outreach efforts, more properties can be tested next year.

Lynn Thorp, national campaign director for Clean Water Action, a national non-profit group that advocates for cleaner drinking water, said states need to increase funding for programs that work to repair or replace lead piping.

“This is something where we can get the lead out,” she said of state remediation programs.

But water, McCarty stressed, is not the likeliest way that children in Philadelphia could be exposed to lead.

“Water is not the primary source of lead exposure for kids. Paint really is,” she said.

Homes built before 1978, she said, could have lead-based paint on the walls, and children could be exposed if they ingest that paint.

At far right, Debra McCarthy, the new commissioner of the Philadelphia Water Department, discusses the steps the utility company has taken to keep lead from Philly's water supply. McCarthy is joined here by Jerry Fagliano of Drexel University's Dornsife School of Public Health and Lynn Thorp of Clean Water Action.

Jerry Fagliano, chair of the department of environmental and occupational health at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health, said lead poisoning is a serious concern.

“I think it’s pretty well-known that lead is a pretty potent neurotoxin,” he said.

He also highlighted the health problem posed by peeling paint – often found in homes in low income or impoverished neighborhoods – which can cause developmental issues in the brains of children.

A panel of experts discussed other potential contaminants to Philly’s drinking water and how the PWD is working to keep Philly’s water clean.

McCarty said fluoride is added to city drinking water – it is commonly used to prevent tooth decay, especially in children – with guidance from the city Department of Health and the American Dental Association.

McCarthy replied similarly when asked about chlorine in the city’s water supply.

“One of the things we work real hard on is making sure we add just the right amount [of chemicals],” she said.

Both McCarthy and Fagliano said the city needs to chlorinate its water to kill harmful microorganisms that would grow if the water wasn’t treated.

"Microorganisms in our drinking water are not a good thing," said Fagliano.

Gary Burlingame, director of the PWD’s bureau of laboratory services, discussed potentially harmful chemicals that have been found in groundwater supplies in nearby communities.

He discussed perfluorinated compounds – chemicals found in fire retardant materials – discovered in public and private wells in the vicinity of the former Naval Air Station Willow Grove in Horsham and the Naval Air Warfare Center in Warminster.

Those compounds are likely in the groundwater near those sites, he said.

Knowledge about the chemicals' effects has been evolving, and the EPA does not regulate them. In 2009, the agency issued guidance on the level at which they are considered harmful to health and said it was assessing the potential risk from short-term exposure through drinking water. It later began studying the health effects from a lifetime of exposure. Those studies remain in progress.

PWD, however, said, does regular testing and no perfluorinated compounds have yet been found in its water sources, Burlingame said.

"We did not see an issue here with the Delaware or the Schuylkill," he said.

Hayden Mitman/for PhillyVoice

Hayden Mitman/for PhillyVoice