November 20, 2017

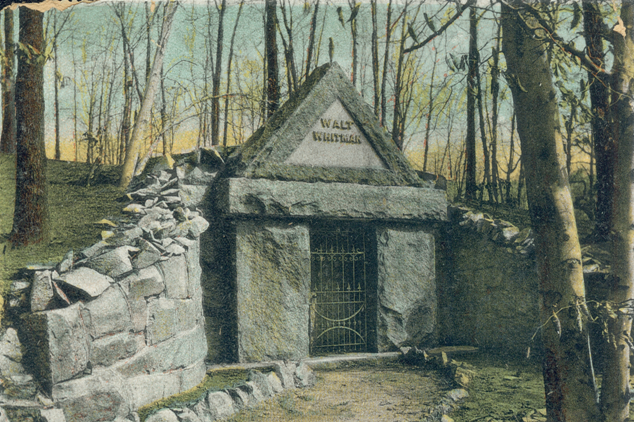

Image courtesy/Camden County Historical Society

Image courtesy/Camden County Historical Society

The Whitman crypt at Harleigh Cemetery.

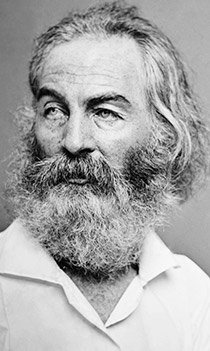

In life, Walt Whitman became Camden’s most famous adopted son, with literary greats – the likes of Charles Dickens, William M. Thackeray, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Bram Stoker and Oscar Wilde – making pilgrimages to his humble home.

In death, Whitman remains the city’s most famous person.

In fact, the celebrity and trend-tracking site PopSugar recently listed his grave as one of the “coolest, most inspiring LGBTQ+ landmarks in the world.” His grave is also listed on other LGBTQ tourism sites. The Guardian newspaper last year called Whitman's collection of poems, "Leaves of Grass," the second most important piece of gay literature ever written.

How Whitman came to rest eternally in Camden is something of a mystery, but his influence and presence is huge for someone who humbly self-published his own poetry in its original edition.

As to his presence in Camden, there’s obviously a massive bridge named in his honor connecting Pennsylvania and New Jersey. That makes sense: In his time, many visitors from Philadelphia took ferries to see the father of free verse poetry at the only home he ever owned on Mickle Boulevard – now across from the Camden County jail.

Despite having been at one time a journalist and then a minor government clerk who viewed government with skepticism and suspicion, a passage from his poetry is boldly inscribed on Camden’s City Hall. That’s despite the fact that Whitman meant New York – definitely not Camden – when he wrote the words “city invincible” despite what local politicians say. And say. And say.

Bottom line: Whitman wrote the line by 1860 – at least 13 years before he moved to Camden. Case closed.

And while Whitman's home in downtown Camden is preserved as a state historic site, the granite mausoleum he designed himself in Harleigh Cemetery, a 130-acre site on the far reaches of Camden and neighboring Collingswood Borough, is his literal and figurative touchstone.

How America’s own Homer came to be buried in the garden-style graveyard, which is downslope from Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center off Haddon Avenue, is a nice slice of local history.

After all, Whitman adopted Camden.

He was a native of Long Island, a former resident of Brooklyn, and then a resident of Washington D.C. during and after the Civil War.

He came to Camden late in life, largely by chance and circumstance after a partially debilitating stroke made living with or near family important, living at first with a brother, George, a former Union officer.

Walt Whitman, as photographed by Mathew Brady.

Cashing in on his literary notoriety, Whitman was gifted with the land for his mausoleum, a marketing ploy meant to make the cemetery more popular.

He used money raised by admirers for the purchase of a summer cottage to instead commission the crypt, which resembles a small house and is set in a hill. Construction took months and cost more than $3,000.

Doug Winterich, the former site manager of the Whitman home, said the poet was absorbed by the construction of the mausoleum, concerned that the massive iron gate at the front remain plumb through the decades.The iron gate, which still swings true, is a favorite place for visitors to place pennies.

“He was involved in most aspects of the tomb,” said Winterich.

Whitman died 125 years ago and was entombed there as were several members of the poet's family.

MORE HISTORY: Martin Luther King Jr. slept there. But did he make history there?

Honored as if he were a military veteran due to his service as a volunteer nurse to Union forces during the Civil War, there’s also a small marker adjacent to the crypt recognizing Whitman's wartime service.

Fittingly, the plot of Camden-born haiku poet Nick Virgilio, a founder of the Walt Whitman Arts Center in Camden, is just across the way from the crypt.

It's as if there is an eternal literary dialogue in one small pocket of Camden.

Source/Library of Congress

Source/Library of Congress