July 20, 2017

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Vidal Rivera, a Camden County police officer and featherweight boxer, trains with his coach, Chris Williams, who is also his mentor and surrogate father.

When not fighting crime as a Camden cop, Vidal Rivera fights in the ring. Unexpected, since Rivera got beat – whooped bad – the first time he boxed.

Up against a street fighter, Rivera had never thrown or taken a punch before. Lots of blood flowed – all of it Rivera’s. He got hit and hit often, though not lastingly hurt. Definitely defeated, though.

Whipped.

His grandmother, who largely raised him while his mother worked in food service jobs to pay bills, had opposed him boxing, but she relented and let him go with a neighbor because she thought “I’d be punched once and quit.”

But the literal 98-pound weakling came back to the gym after his drubbing to practice and practice more.

While boxing kept pulling him back, his second, third and fourth fights with the same brawling opponent ended the same way.

“Massacred,” he recalls. Badly beaten because he tried to win by “burrowing in and slugging it out.”

The fifth bout for the fledgling fighter, who could not do a single pushup when he entered a boxing gym at the age of 14, seemed headed that way, too.

His epiphany came in the third round: Rivera discovered he was not a fighter, after all.

No, Rivera was something better – a boxer. He could move in on fast feet, make contact, move out gracefully, slipping blows.

And do it over and over again.

His opponent "never touched him again,” recalls his coach, Chris Williams.

“BOOM! The light came on!” says Rivera, shaking his head over lessons learned the hard way.

“He had not an inkling,” when he arrived at the Camden Boxing Academy School of Excellence, says Williams.

Mentor Chris Williams looks on as Vidal Rivera moves around the ring during a recent training session.

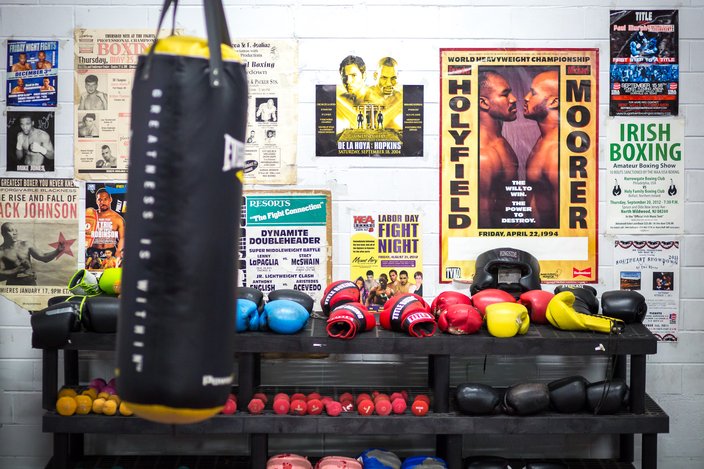

William’s gym with the grand name looks like an abandoned warehouse from the street. The building is a former pickle factory and once illicit go-go bar in Centerville, a tough neighborhood with a household income lower than much of the rest of Camden.

The gym draws children as young as five and a cross-section of Camden’s nationalities. Williams has schooled Rivera for 11 years, the last four at this location after getting displaced from a city-owned recreation center.

“He didn’t understand the difference between boxing and fighting. Sometimes, the light comes on,” says Williams.

Vidal Rivera arrives at the gym for a recent training session following a patrol shift.

Williams was himself a gifted amateur whose plans to turn pro ended two weeks before his first paid bout with Joe Frazier Jr. when an accident required about 200 stitches in just one hand.

Now Williams fights through his protégé, “the best fighter I’ve ever had” out of more than 1,000 students of the sweet science, he says, including a top-ranked female boxer.

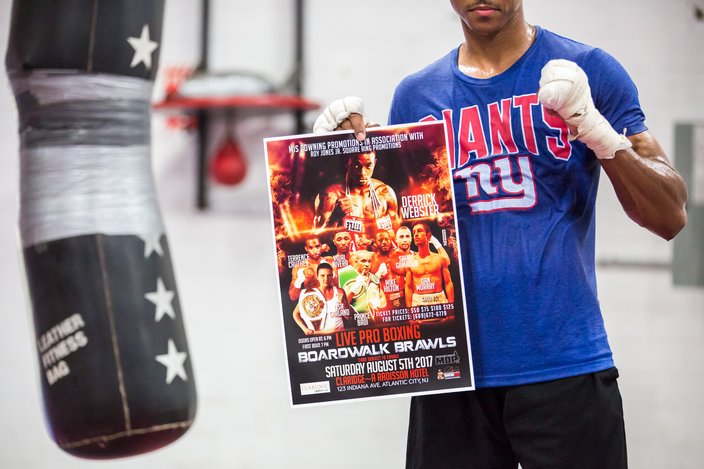

A featherweight now at 124 pounds and ranked in the 500s, Rivera has nine Golden Glove amateur wins and six wins as a pro. There’s an upcoming bout Aug. 5 at the Claridge in Atlantic City. And then maybe another later in August.

"This kid is easy to market," says Catherine Lebron, a vice president at Mis Downing Promotions. Tickets to see the eight bouts range from $50 to $125, though there are few pricey VIP seats, too.

Miguel Figueroa, assistant to Rivera's head coach, works closely with the featherweight during a recent training session.

She has watched Rivera in a seven-round sparring contest and is impressed. "He's tough. He has the footwork. He's a boxer, but he can fight toe-to-toe. He has a bright future," said Lebron.

Rivera's first purse of $700 was for a TKO originally slated for four rounds. It ended in just over two minutes.

Now he’s boxing six-round fights and paydays have stepped up, but not hugely.

He knows his personal narrative is part of what sells him – he uses the word “ghetto” to describe where he’s from.

Rivera also understands the narrative thread that he’s proudly from Camden, the adopted hometown of famous heavyweight boxer Jersey Joe Walcott, a tough town where Rivera has worked a police officer for the past two years.

The boxing gym at 714 Florence St. in Camden is loud, sweaty and bustling with energy.

He knows his story sets him apart.

Rivera cautiously admits he’d like to be a boxing “superstar” – a tough goal in his weight class and with interest waning in boxing overall.

He also adds he hates gambling, a serious aspect of the sport.

“If you stay humble, you don’t stumble,” he says of balancing his aspirations with reality.

Coaching assistant Miguel Figueroa laces up Rivera's boxing gloves.

Handsome, personable, well-spoken, Rivera tried out the nickname ‘Hitman,” borrowed from his favorite boxer ever, legendary Thomas “Hitman” Hearns. And while the hitman nickname and Rivera’s picture is on his coach’s business card, Rivera’s settled on a nickname to keep him grounded, drawn from his roots.

CAMDEN – in all-caps – is on his trunks. Rivera fights as the “Pride of Camden.”

“It’s something I can run with.”

A delivery of newly-printed posters promoting Vidal Rivera's upcoming match arrived partway through a recent training session in Camden.

He’s convinced he will one day fight for a title and become wealthy enough to buy homes for members of his family.

Meanwhile, on top of the 15 hours he devotes to boxing each week, there’s the full-time job as a $38,000 police officer patrolling his city.

Before that, he worked as an police analyst, observing the city from surveillance cameras blanketing much of the town, aiding police with deployment and responses.

He thinks of his law enforcement work as “positive and new” but he also knows much of the city, particularly his generation, resents police.

The walls of the gym in the Centerville section of Camden are covered with dozens of boxing event posters dating back to the 1990s.

“I’m trying to show them by how I do it: walking a beat, being involved, going to school events. I’m trying to fix it. Being what policing should be,” says Rivera.

Even if his boxing dreams come true and he leaves the force for a time, Rivera plans on returning to law enforcement when he retires in his early 30s, knowing boxing careers have short shelf lives.

After all, Wolcott became the sheriff of Camden County following the end of his boxing career.

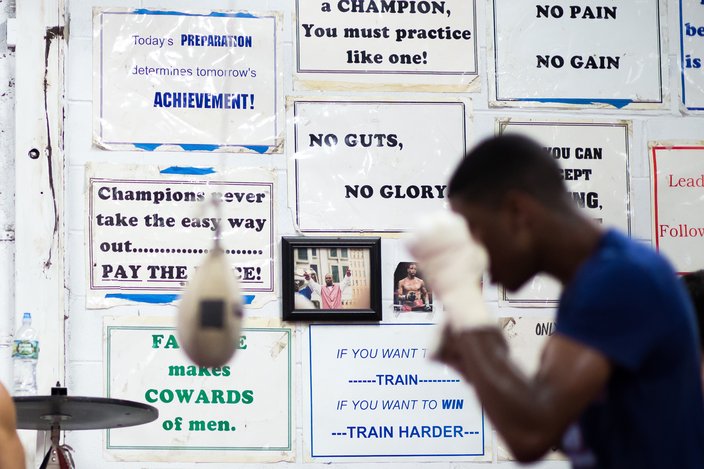

Vidal Rivera, who fights as “The Pride of Camden” and works as a police officer, is surrounded by motivators in his hometown.

Williams is convinced Rivera is a contender.

“He’s going to the top,” says the coach, who works silently with Rivera so he can think for himself and adapt in real time.

Like his coaching partner, Denny Brown, Williams spends about $500 a month out of his own pocket just to keep the boxing gym open – in case another scrawny 14-year-old with raw talent comes through the door, hoping to become the next pride of Camden.

For now, however, Rivera is his focus.

“He has the personality and the skills to match,” Williams says.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice