November 10, 2016

Courtesy/UFC

Courtesy/UFC

Dave Sholler, center, is the only thing standing between UFC featherweight champ Conor McGregor, left, and opponent Nate Diaz during their pre-fight press conference earlier this year.

The tiny cream-colored, red-trimmed trailer that sat up on four cinder blocks was about as clean as four kids could get it. There was a stash of balled-up newspapers there in one corner, and some old, dog-eared magazines piled up in another. The matchbox kitchen had its usual assortment of dishes, spoons and forks lying around that needed scrubbing. Climate control wasn’t part of it, either.

When the space heater worked, having the top bunk meant a toasty slumber. Everyone else required heaps of blankets. The holes in the walls of No. 4A, at 5043 English Creek Road, in Egg Harbor Township, N.J., were covered with a wood board and caulk. Otherwise, a natty pillow or blanket would do.

A musty, smoky odor pervaded the 7-foot long-by-2-foot wide living space that was more an incubator of love, tolerance, commitment and wrought-iron will.

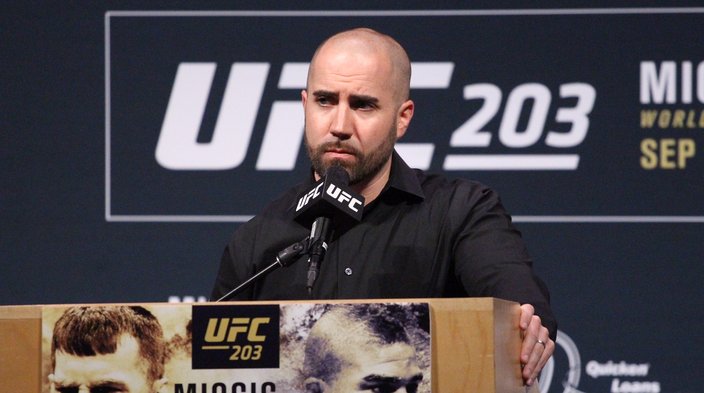

Ever notice the stubby, bearded bald man on stage at major UFC fights standing between two of the fiercest fighters in the world? He never seems frazzled, does he?

That's because Dave Sholler learned early in life that if he was able to get out of “4A,” there was nothing that could rattle him — not even being thrown off a stage by UFC superstar Jon Jones.

Today, Sholler, 32, is one of the top public relations executives in professional sports. On Saturday, during the historic UFC 205 at Madison Square Garden, in the first-ever major UFC event held in New York, Sholler will be taking his final bow as UFC’s senior vice president of public relations and athlete marketing and development. Right after, he’s coming home to become the Philadelphia 76ers new vice president of communications.

“It was important for me to come home again, but it was a difficult decision to leave the UFC, because I’ve built lifelong friendships and relationships in the UFC and this line of work has helped make me who I am today,” said Sholler, an Egg Harbor High and Stockton University graduate. “I made the decision based on a couple of areas. First and foremost in my life, family has been No. 1. My twin daughters are almost four years old and wanted the chance to raise them around my family. I want them to root for the Eagles on Sundays, and sit courtside at the Sixers. My wife Tiffany is from South Jersey and her family is still there.

“The second reason is the Sixers. I truly believe that they’re building and going in the right direction. I truly believe what Scott O'Neil and the Sixers are doing. And third, this has been a dream for me to come home and be a part of a major sports franchise and be on that float coming down Broad Street when they win a world championship. It was a difficult decision, but having my family there helped me make the choice."

Sholler has spent a life filled with challenges — starting in that trailer he still refers to as “4A.”

“I firmly believe that if I didn’t go through what I did, I wouldn’t be where I am now,” Sholler said. “I had nothing, but I learned from having nothing. Where we lived we liked to call a mobile home, but the truth is, it was trailer on cinderblocks—and it was embarrassing to let anyone know we lived there. My father was a drug addict and my mom, God bless her, worked 70 hours a week. We would see her in the morning before we went to school and wouldn’t see her again until she came home later that night.

"As a kid, if you live through that, you have one of two choices: Either you become a statistic, or you don’t. It would have been very easy for me and my siblings to be another statistic. The odds were certainly stacked up against us. But I’ll tell you this, statistics be damned; statistics be damned. It's strange to say, but I wouldn’t change anything. Not a thing.”

George David Sholler had his demons. They could start at 8 a.m. or noon. It didn’t matter. The stupor would morph one day into the next. With each sip came distance, mixed with a touch of depression. This placed George’s oldest son, Dave, in a precarious spot at a very young age. George’s devil was alcohol. In addition, opiates, specifically oxycontin. As Donna, George’s wife, was trying to make ends meet as a waitress at a local deli working from sun up to sun down, Dave was forced to fill the missing void, serving as big brother, father, tutor, counselor, coach, and bedrock to younger siblings Jill, Dan and Dennis.

The four were inseparable. They would go over each other’s homework, encourage one another in their outside endeavors and play a game of keeping a secret from the rest of the world: They didn’t want anyone to know where and how they lived.

“As a kid, you don’t know, you think the way you’re living now will never end and that you’ll would be there forever,” recalled Dan, 26, a Penn graduate who is a Ph.D. in information science at the University of Texas. “We never had friends over. We had a lot of pride and we were certainly embarrassed by where we were living. The bus dropped us off and word spread we lived in a trailer park. We got called ‘trailer trash’ dozens of times. When I was younger, I was ready to throw down with anyone. We all hated it. But it just rolled off of Dave.

“We spun it around. We actually used it as motivation in school. We had no control over what kids outside thought. But every time I hear that term ‘trailer trash’ I still cringe. People use the term to hurt. We were trailer kids, we wear it as a badge of honor. Dave handled everything. He had a better grip at 10 of what was going on more than most adults. He tried to shield us from the things happening to my father by selectively telling us what was going on. We all followed right behind him. He showed us the best way to grow up quick and get through major problems.”

One of those problems occurred one weekday after school upon arriving back at 4A. Dan and Dave noticed plastic wrappers and EMT paraphernalia on the living room floor. The boys often had to pick up their father after a rough night and put him to bed. This was different. There were remnants that something went on, but what happened was anyone’s guess. There was no body, no proof. Dave knew what to do immediately.

“Dave checked the hospital plastic and got the name from there to see if my father was admitted,” Dan recalled. “My father had almost overdosed and called the ambulance himself. No one could get a hold of my mother, so Dave handled it. He was probably 14, a freshman in high school. He was so calm. He never panicked. I was in third grade, and I remember I was freaking out.

My grandfather grew up in the Juniata section of Philly and he had this motto that I still repeat to myself every day: ‘It doesn’t matter whether you have to shovel sh*t, you always have to find a way to provide for your family.’

“He made the decision of my father’s care, and it’s something that I’ll always remember. He put the pieces together and figured out a way forward. He did that time and time again with my father, with the whole family. He was the rock. Sometimes Dave used tough love, and if I was overly emotional and crying, he knew how to respond, and he could tell when I was hiding my emotions. I always felt like everything was always going to be all right, because we had Dave, and he was going to spearhead the problem and take the brunt. Hell yeah, you have no idea how proud I am of him. Every step he’s taken he’s been successful at what he does. There was addiction all around. We knew we could easily be one of them. We always had, I would say, a family motto: ‘F the statistics.’”

The nadir came when Dave had to finally admit his father to rehab. Nothing around Dave that day was audible. He could hear himself breathe. That was about it. He was around 18 then, placed in a spot no son should be placed in, feeling like an extra in a scene from “The Walking Dead.”

As he moved slowly down the narrow corridor of the facility, he tried looking forward, though the nerves on the back of his neck kept telling him eyes were on him. He felt like an outsider, because he was, surrounded by hollow, lost souls grasping for any morsel of normalcy they could find. Each step Sholler took came with a reminder to himself, From this day forward, whatever it takes to get out of this life, I’m going to do it. I can’t keep this path going for the family.

You go through life stapled to certain events that change everything. For Dave, this was one of them. The day his mother was fed up with the station in life her husband took. The day Sholler took on the responsibility of signing his father into a drug rehabilitation center. Either do that, or let him go.

“That was it, that was rock bottom for me, that day I signed him in, because I saw firsthand how drugs destroy lives, and it wasn’t going to happen to us,” Dave said. “Thank God for my [maternal] grandfather [Don Wadley]. He helped all of us get through it. There was a lot of bad around us, but there was also a lot of good. I was fortunate to have good grandparents on my mother’s side. I also remember the different holidays. I remember the pain in my mom’s eyes when she couldn’t do anything. The woman busted her ass for us. My mom tried so hard, if it weren’t for the neighborhood and the people that we got to know through recreational sports or through school, I’m not sure we would have the Hallmark card style holidays. The holidays are really important for me.”

It’s why every holiday season, Dave seeks out a family in need and provides for them from start to finish. He won’t yell from a mountaintop that he’s doing it.

Only he knows, and that’s good enough for him.

Sholler worked at Wawa through high school and graduated Stockton University in 2006. For the next three-and-half years he did everything from freelance writing for various boxing and mixed martial arts sites, to working special events for Harrah’s Entertainment, now Caesars Entertainment.

He took care of VIPs. He ran copy to press row during major fights. He slung turkeys from the back of a truck during Thanksgiving Day special events. He interned with the Sixers when he was 19, and his goal was to always go back and work for a major pro sports team.

He just took a very circuitous route to arrive.

Dave’s big breakthrough came when he began working for Tom Gerbasi, of UFC.com. They immediately clicked, because Dave was willing to cover or take on any assignment.

“A lot of my work ethic comes from my mom and grandfather,” Dave said. “My grandfather grew up in the Juniata section of Philly and he had this motto that I still repeat to myself every day: ‘It doesn’t matter whether you have to shovel sh*t, you always have to find a way to provide for your family.’ He kept telling me if I keep grinding it out, it’s all going to work out one day. He died in 2010, but before he passed, I remember looking him dead in the eye and telling him, ‘Don’t worry grandpop, one day, I’m going to come home and be part of a championship Philadelphia team.’ I still believe that in my heart. I think back to the lessons I learned from my grandfather. They’ll never go away.”

We wanted to change the outlook for our families. We’re not there, but so far, we’re on our way. I don’t know where it’s going to go, but you better be damned sure it won’t be trailer parks and drug addiction.

Neither did Dave.

In 2009, Gerbasi told him a position was opening in PR in World Extreme Cagefighting (WEC), which was owned by Zuffa, then the parent company of UFC before Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, and Dana White sold it to WME-IMG in July for $4 billion. Dave started at WEC in 2009, and by January 2011, became the PR man for UFC.

“I heard every story and every background, so when I heard Dave’s, I appreciate folks like him,” Gerbasi said. “You have people bitching and moaning where they came from, but I appreciate guys more from tougher backgrounds that made something of themselves, just by putting their heads down and grinding. I may have opened the door for Dave – but he kicked it down. Now look at him. He treats the guys from the lower part of the media ladder as he does guys from the top. Dave never forgot where he came, as most successful people do.

“He’s a fighter; a kid who wasn’t handed anything. He doesn’t have an Ivy League degree. He didn’t have an easy route, and when I see a guy like that, I love it. I don’t take an ounce of credit for Dave. He kicked down the door. He did something good for himself. He was not in an easy spot with UFC. He wasn’t able to please everyone all of the time. For him to be in the high pressure spot for as long as he was, a lot of long hours, a lot of 2 a.m. phone calls, a lot of time away from his family, if they survive that, they’re the real deal. Dave’s the real deal.”

That's why when he leaves for the Sixers later this month, White, the sport's most powerful figure, knows he won't be easy to replace.

Said White, “I think that Dave Sholler has become one of the best PR guys in all of professional sports. He knows his stuff and is passionate about what we do. I don't listen to many people, but when I know Dave is serious about something, I listen. It’s extremely hard to see him go.”

As for the rest of the Sholler family, they're following the path forged by their older brother.

Jill, 30, is a Stockton grad who lives in South Jersey. The two younger boys are at Texas, where Dennis, 23, a Rutgers undergrad, is working on a Ph.D. involving the hard science of what drug addiction does to the brain, and Dan is aspiring to be a college professor.

“Myself, my brothers and sister have a word tattooed on us, ‘Dynasty,’ as corny as it sounds,” Dave said. “We came up when dynasty was a word we saw everywhere in the sports world. We all said to ourselves that whatever we do, we have to find a way to create a dynasty among each other. It means to most people wealth, or power, or whatever.

"What it means for us is changing what the Sholler name would mean for our kids, and our children’s children. We wanted to change the outlook for our families. We’re not there, but so far, we’re on our way. I don’t know where it’s going to go, but you better be damned sure it won’t be trailer parks and drug addiction.”

Follow Joe on Twitter: @JSantoliquito