December 23, 2015

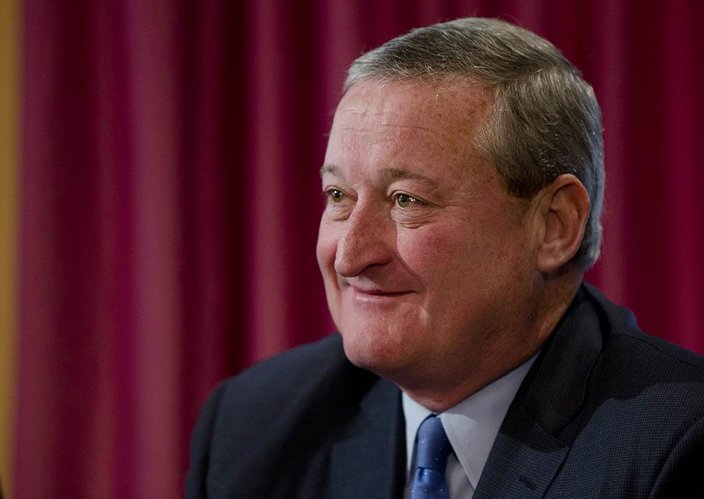

Photo courtesy/Jim Kenney

Photo courtesy/Jim Kenney

Jim Kenney chats with Eagles fans on a playground in South Philadelphia. As a kid growing up in the 300 block of Cantrell Street, Kenney and his friends would play day and night on the playgrounds of South Philly. "Jimmy was one of those who got along with everyone," says his good friend, union leader John Dougherty. "He was always pretty consistent, whether that was with the tough guys or the smart guys. He could talk to and relate to everyone."

His hands are always moving.

Clasping. Clenching. Pointing. Gesticulating.

Jim Kenney can’t sit still.

The new mayor-elect of Philadelphia has never been able to sit still. Not since his days on the 300 block of Cantrell Street, in a neighborhood where rowhomes are bunched together so tightly that they look like great red-brick accordions. Not since the neighbors could walk into the house next door without knocking in fear of getting shot, when streets would be filled during the summer with kids playing.

Kenney’s political career was forged in this crucible, at the kitchen table of a fireman, his father James, and Barbara, a working mother. Kenney, to some degree, was the Irish Catholic South Philly version of the precocious “C” character in “A Bronx Tale.” A google-eyed, street-wise kid who absorbed everything around him – getting two educations. One from the priests and nuns who used to teach him at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, on Third Street, and the rigid Jesuits espousing service to others at St. Joseph’s Prep, on Girard Avenue.

"I would say Jimmy is a cross between his mother and father. They’re both very articulate and very driven. His mom was one of those people when she was involved, she was out in front....His political career started at their kitchen table." – John Dougherty, union leader and longtime Kenney friend

And the other education from the assorted characters he came across, like “Chicken Armed Louie,” and the patrons who would frequent the corner bar his grandfather tended, to the guys from around the block, like union chief John Dougherty, who grew up with Kenney and went on to his own success.

On Jan. 4, Kenney, 57, will be sworn as in the 99th mayor of Philadelphia. But he wouldn’t have arrived here without the early influences he received from the “Two Street” neighborhood, where he learned loyalty, coping, courage and the people skills to connect with others who were different than him.

Kenney’s early memories of his household were knowing when his father was home. The pungent smell of burnt wood and rubber would waft through the small house, signaling dad was theirs for four days in his four-on, four-off rotation. There was the constant humming white noise of a fire department dispatch radio that would drive his mother up a wall, because his father had to know what was going on.

What young Jim didn’t realize was that he was sharing his father with the world. The Kenneys were familiar with the dangers James faced each time he stepped out of the house to head to the firehouse. They just refused to obsess over it.

“On my father’s days off, he had additional jobs. He was an usher at the Spectrum in the late 1960s, early ’70s. He delivered flowers. My mother worked at a bank for a long time, and part-time in the advertising department of The Inquirer and Daily News, in addition to raising four kids – me, my brother Stephen, sister Janet and brother Chris. They’re remarkable people and it’s where my work ethic came from. We were busy, out all of the time. We’re not talking about the video game generation. When you were off from school, you were out in the street from 9 in the morning to early evening. We all knew what my father did and how dangerous it was. But it wasn’t something we pined about on a daily basis.”

There were the scares, like the time his father fell through a floor, and the other time his arm was badly scraped. But he wouldn’t say anything to Jim or his siblings about it. It was part of the job, part of sacrificing himself for others that he ignored the small ember holes that pocked the cotton pants firemen wore in the 1960s and ’70s.

Besides, Kenney was preoccupied with his full schedule, delivering The Inquirer in the morning, washing dishes at a local Italian restaurant and never being allowed to stay in bed past 9 on a weekend.

“I hated that (paperboy) job,” Kenney says, laughing. “But you had to do it. You splash water on your face and you go out the door in the cold, the heat, it didn’t matter. You had to do something in my house. In college, I remember working at Einstein Medical Center. I greeted people, gave directions, and had to release bodies to undertakers on the weekends, going in and checking toe tags.

“When they were indoctrinating me, on the last leg of my orientation there was a body on a gurney in the hallway with a sheet over it. I walked by it and the guy giving the tour banged the body. It jumped up. I ran like hell. I didn’t look behind me, I don’t think my feet touched the ground. It wound up being a security guard under the sheet. But it was my responsibility, you had to do it. Even if you didn’t want to do it.”

Like attend The Prep.

Kenney had thought he would join his friends at St. John Neumann, where most Catholic boys in South Philly went to high school. He resisted his parents’ wishes to attend the Jesuit high school.

“I told them that I didn’t want to go to Prep,” Kenney recalled. “My parents weren’t too happy about that. They worked two, three different jobs each so I could go. They told me to give it a year. If I wasn’t happy after a year, I would go to Neumann. It wound up being a good experience; one of the best social, educational experiences that I ever had in my life. It wasn’t just one neighborhood high school. It was a mix of kids that would have gone to (Father) Judge, (Archbishop) Ryan, and North Catholic. I got to interact with kids from the suburbs.

“I remember one disgusting story of a man who had his penis bitten off by a woman in that [neighborhood heroin] house. He came running out with blood spurting all over the place, but it happened. When they finally got out, they moved around the corner to the 40 block of Winton Street, and that’s where Chicken Armed Louie got beaten to death with a baseball bat. When they carried his body out, the neighbors cheered from their front steps."

“It’s the first place I got to interact with African-American students, through the Fischer family (and Gino scholarships). One of the problems with Prep now, if it has a problem, is that it’s less diverse than it was. There is less of a city flavor, less of an African-American, minority flavor. I met some really cool kids that went on to have very successful lives at St. Joe’s Prep. There was a black culture club there that was interesting; a lot of kids were in it. It was good for the school, and good for all of our life experiences today to interact with people that are different than we are.”

The building blocks of his political life had already begun to emerge.

“I always thought Jimmy had leadership skills; he was always an independent thinker,” Dougherty said. “When we all went to The Prep, I couldn’t wait to get home. Jimmy didn’t. He had friends everywhere. His mom and my mom were extremely close. Everyone stopped in his mother’s house like they would mine during the holidays. I would say Jimmy is a cross between his mother and father. They’re both very articulate and very driven. His mom was one of those people when she was involved, she was out in front.

“His political career started at their kitchen table. Jim has been at the forefront of something as simple of getting kids into a school, to even now, he gave me the names of 19 children, with specific ages and sizes, to help out during Christmas. Years ago, he had his fingerprints on local sports teams getting equipment and uniforms. Jimmy took his Jesuit education very seriously, doing for others and never letting anything get in his way.

“We would hang at the playground as kids playing from morning to night. There would be hundreds of kids in that park playing all day. Jimmy was one of those who got along with everyone. He was always pretty consistent, whether that was with the tough guys or the smart guys. He could talk to and relate to everyone. It’s really a gift that came from the house, from James and Barbara.”

The neighborhood was far from idyllic. It couldn’t completely insulate itself from the outside world. Drugs infiltrated Kenney’s small South Philly nook. He knows about six people whose lives were lost to drug use, or because of drugs. On his own block, there was a heroin house where junkies would come and go. Even the 300 block of Cantrell Street wasn’t immune to the tensions of the times.

“The dealer in the heroin house on my block was a guy we called Chicken Arm Louie, because he had a withered arm,” Kenney said. “Drugs took everyone in and out of that place. There are at least six kids I knew around my age all dead now or affected because of drugs. My area wasn’t a drug area. But heroin was a pretty heavy thing in the 1970s. The neighbors would try to deal with it. You have a summer night and the street was full of people, some coming in and out of that heroin house. Guys would drive up and buy their drugs, and the neighbors would slash their tires.

“I remember one disgusting story of a man who had his penis bitten off by a woman in that house. He came running out with blood spurting all over the place, but it happened. When they finally got out, they moved around the corner to the 40 block of Winton Street, and that’s where Chicken Armed Louie got beaten to death with a baseball bat. When they carried his body out, the neighbors cheered from their front steps.

“The drugs brought an element to the neighborhood that was unsavory. But they never broke into any houses. They may have broken into houses somewhere else, but not on that street. There were some tough guys on that street and they knew that. For the most part, the neighborhood was solid. There was some racial tension. I remember some people supporting George Wallace, and I was like, ‘What, are you kidding me?’ It was very an Archie Bunker-ish, pro-Vietnam War era. There were a lot of young men killed in action in Vietnam in that neighborhood. It was typical, the 1960s-70s was a stressful experience, filled with segregated areas. I mean I had to run through certain neighborhoods. It was a nitty-gritty, lower-middle class neighborhood. You had to go to college or get a job.”

In less than two weeks, Jim Kenney will take the oath as mayor of Philadelphia. His parents will be there. So will probably everyone he’s ever spoken to growing up in South Philly. Kenney will no doubt leak.

“I get emotional all of the time, I’m always crying about something. But my parents being there is very special for me,” he said. “I’m very, very happy and thankful that they are still alive to see this. My mom was 19 when I was born. She’s 75 now. My father is 80 and will be 81 in July. To have them both is very special. They married young in those days.

"There is a saying in my neighborhood that the second baby takes nine months and the first one can come at any time. They were married in October, I came along in August. So I made it — I made it.”

Yes, the kid from the neighborhood has made it.