March 03, 2016

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Deen Kogan, co-founder of the Society Hill Playhouse stands in the entryway where dozens of artist set renderings and neon signs hang.

Deen Kogan's belongings were already packed and on their way to Pittsburgh when she got a call from Temple University.

"'Dr. Hunter wants you in his program,' they said to me," Kogan told PhillyVoice, recalling a phone conversation with the registrar.

She ardently applied for admission in what was then the "Radio Theater & Television" program at the university, despite being told the then-new head of their department, a man with high standards, was unlikely to take in a freshman like her. She eventually gave up and settled on Carnegie Tech.

But when that call finally came, last-minute as it was, she changed course without hesitation. Importantly, that moment would also change the course of Philadelphia's theater community: She fell in love with her husband, Jay, also a Temple student, on her first day of class and similarly became too enamored with the city to ever leave.

What resulted was six decades of investment in Philadelphia.

Society Hill Playhouse, a staple of Philadelphia theater since Kogan purchased the theater with her husband (deceased since 1993) in 1959, will be demolished in the months ahead as the Conshohocken-based Toll Brothers ready 20 luxury apartment units for the 507 S. Eighth St. property. Following this weekend's final stage performance with "Liberty City Radio Theatre," it will end an era of wide-ranging plays and programs selected and nurtured by Kogan, who long ago nestled into the theater as her "second home."

Yet, as the books get harder to balance, the theater community outgrows comparably small and obscure operations like hers and she clocks in more birthdays, she has, in truth, made peace with departing from that home.

“I’ve done this for a long time, and there’s not much support anymore," she explained, frankly. "And you have a different attitude. I love young people, but in this field you meet more of 'Me, me, me!' To work in theater, you need an ego, but there’s a limit. And I think that’s basically it: Society has changed.”

Though, that's not to suggest it isn't difficult to greet the end of a lifetime's worth of work.

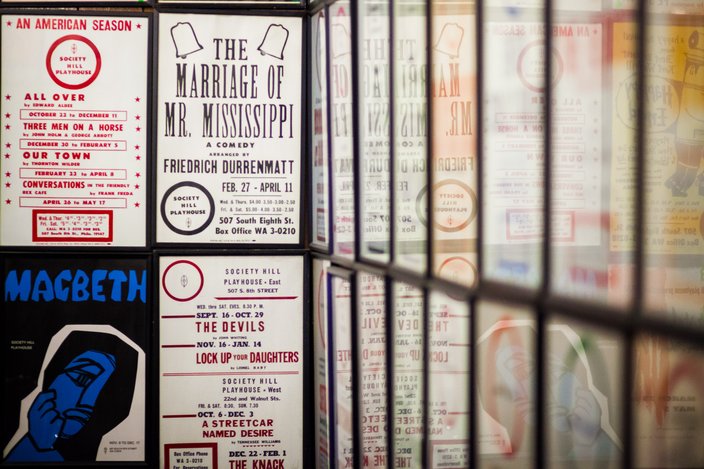

"Incidentally, closing is not very happy," she mused, overlooking a wall of play posters that hang in the theater's gallery space (the posters will be sold at a yard sale on March 13). "I'm not happy about it, but there's nothing that lasts forever."

Performance posters dating back to the 1960s, when the playhouse had its first season, completely line the walls of one room.

The theater has undeniably struggled in recent years, as the theaters lined up on Avenue of the Arts continue to grow and change the name of the game, and funding for the contemporary American and European plays she seeks out becomes more scarce. Still, the playhouse has hardly come and gone without making a monumental impact on the city's theater community -- or culture in general.

In the 1960s, following the death of Martin Luther King Jr., the playhouse hosted the first integrated cast in Philadelphia with "Street Theater." Kogan described the move as "frightening" at the time, unsure what reaction to expect from audiences in a city that was very much segregated by neighborhood.

The playhouse's first full season in 1960, meanwhile, included large-cast Irish productions like Brendan Behan's "The Quare Fellow," unusual for the time. Other notable productions include pieces like German writer Peter Weiss' "Marat/Sade" play about the French Revolution (one of Kogan's favorites), Max Frisch's "The Chinese Wall" and Picasso's "Four Little Girls."

Society Hill Playhouse, located at 507 S. Eighth St.

All this, of course, in addition to any number of locally written works the playhouse premiered, in the spirit of giving just about anyone with a script and a solid work ethic the chance to shine.

"There’s more diversity going in and out of the doors of Society Hill Playhouse than any other theater in town," Susan Turlish, who got involved with the theater in its early years as a 14-year-old student, told PhillyVoice. "When you put it all together -- the longevity, the number of plays, the different kinds of plays, the outreach to different populations and neighborhoods -- there was more diversity than in any theater in town ever.

"That’s what I would say made the playhouse what it was: Its public nature. Deen and Jay always saying, ‘Come in.’"

The playhouse was also a trailblazer and model for many of today's programs that bring theater to the masses. The 1901-constructed building has a history as a theater for pieces funded by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration under the New Deal, which compensated unemployed artists (among others) to contribute to public spaces.

The building which houses the Society Hill Playhouse is historic, having been built in 1901. The tin walls and ceilings in the upstairs 'Main Stage' and the 'Red Room' (pictured) are completely original.

In their own way, the Kogans would continue that theme of public-geared work in the 1970s through the 1990s with Philadelphia Youth Theater (PYT). It was a sort of theater camp that joined together youth from the Philadelphia School District, parochial and private schools to learn play production, dance, acting and set design, as well as create three productions per school year.

“There was a time when everybody in the city participated in what it had to offer, and not just because you had the money to buy a ticket to the theater, or opera or art museum," Turlish, who headed the PYT program, explained. "[That program] enriched me as a human being, and I know for all the people who participated -- when you think of those kids who went through PYT or [our summer program], all of them, they’ll never forget it."

Kogan said the theater has always operated under the belief that it exists as a producer of work that mirrors society. The playhouse extended that belief well beyond the arts, too, offering up its space several times for memorial services and, once, for a same-sex wedding well before it was legal.

"The theater's mission, if you want to be fancy about it, was to serve the community, not a community," Kogan explained.

The theater's most popular production through the years was likely "Nunsense," a musical comedy about a group of nuns raising money to bury their fellow sisters through a kitschy auditorium performance. Kogan expected it to run for five weeks when they first premiered, but it hit with audiences in a big way and ran in the theater for 10 years, spanning the mid-'80s to mid-'90s. It was a production that, Kogan said, kept them afloat for many years.

"It's a piece of fluff, but a cute piece of fluff," Kogan said, smiling.

The 'Main Stage' at the Society Hill Playhouse seats 223 at full capacity.

And though her days of picking out massive 60-cast-member productions are over, she's not exactly closing the curtains once the playhouse is demolished. She plans to operate small productions -- stage readings, cabarets, burlesque shows, etc. -- at Port Richmond Books, a business she owns at 3037 Richmond St. that was previously a movie theater. (And, thus, has space for performances.)

"She’s not one to rest on her laurels," Greg Gillespie, who manages the bookstore and was first hired by Kogan as an actor for "Borstal Boy" at the playhouse in 1973, told PhillyVoice. "I feel terrible the theater is closing -- it has to be heartbreaking for her. But she's a realist; she's very pragmatic, and she knew it was time to do it. And now she has something new to explore."

Kogan will also host a noir convention in October, a tradition she's carried on since hosting massive mystery novel conventions with her husband in decades past. To boot, she's throwing a goodbye party on March 25, open to anyone who's been involved with or impacted by the playhouse through the years.

To preserve the history of the building, which was never designated as a historic building ("I couldn't do anything [to the building] without permission if I did that," Kogan explained, citing Isaiah Zagar's playhouse mural), Kogan is donating materials from the playhouse to Temple University's Paley Library archives. Many of the playhouse's iconic neon signs will go to a museum.

Kogan has always had a liking for Dobermans. Here, Tonka greets visitors while very much wanting to be part of the action. (A neon sign that reads "Tonka," Kogan said, is the only one that won't be donated.)

But she hopes the playhouse will truly be preserved in the memories of those it's touched.

“I want audiences to remember the plays, and some of what they -- I hope -- learned, and I want actors to remember what they learned," Kogan said. "I want them to remember they had a good time. And that we had a good time.”

Turlish, meanwhile, is working on securing a Wikipedia entry for the playhouse, to educate people about a cultural staple that, she said, would be near impossible to ever replicate and will be sorely missed.

"When I think about this building not being there anymore, I think of so many people who'd come in and say ‘Do you remember me?’ They’d come back, and this or that would have changed, but it'd be there," Turlish said.

"People who come back and see condos are going to be very confused.”

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice