June 23, 2016

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

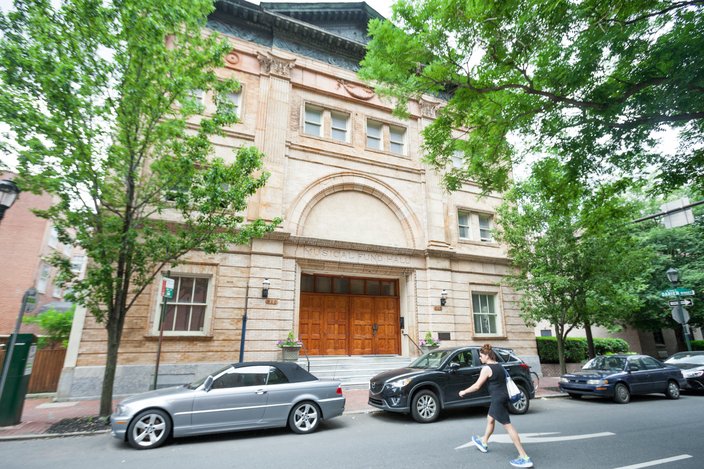

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission marker outside, Musical Fund Hall, 808 Locust St., notes the location hosted the first Republican National Convention in 1856..

Philadelphia will serve as an appropriate backdrop when the Democrats coronate Hillary Clinton as their presidential nominee late next month. The city shades overwhelmingly blue, with registered Democrats outnumbering Republicans by nearly 8 to 1.

By contrast, the political tenor of the city was very divided in 1856, when the fledgling Republican Party hosted its first presidential nominating convention inside Musical Fund Hall at 808 Locust St. There, a patchwork group of politicians united around a platform opposing the westward expansion of slavery.

As the Civil War grew near, Philadelphia boasted a vigorous anti-slavery network. But it also was home to many people sympathetic to the South, thanks to varied familial, intellectual and economic connections. The city even had a small secessionist newspaper, The Palmetto Flag.

"That reflected the character of the nation, of how torn apart it was," said Randall Miller, a history professor at Saint Joseph's University.

There have been 11 political conventions held in Philadelphia, dating back to 1848. Each of them are detailed as part of an ongoing exhibit, Sweeping the Country: Political Conventions in Philadelphia, at The Heritage Center of the Union League of Philadelphia.

The 1856 Republican National Convention stands among the most notable.

"The 1856 convention in Philadelphia, one could say is the real spawning of the Republican Party in terms of its presidential ambitions and prospects," said Miller, who contributed a video segment to the Heritage Center's exhibit.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceMusical Fund Hall, 808 Locust Street.

The Republican Party had formed two years earlier as the Whig Party fractured on slavery, the predominant issue for much of the 19th Century. It brought together a coalition of groups: abolitionists, former Whigs and Democrats who opposed slavery for various reasons, and Free Soilers, a group that believed free men working on free soil constituted a better economic system than slavery.

Their viewpoints differed on virtually every issue, including slavery, Miller said. Some found slavery morally reprehensible. Others found it impossible to compete against economically. Some feared the political imbalance it provided the South.

But the group coalesced around a shared viewpoint – they all opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which enabled residents of new territories to decide whether to permit slavery.

"The one thing that people could agree upon was to keep slavery from spreading," Miller said.

Four months prior to meeting in Philadelphia from June 17-19, 1856, the Republicans held a national plenary convention in Pittsburgh. There, they stated their opposition to the westward expansion of slavery and affirmed their support of a slavery-free Kansas.

"People wanted to move there and set up their farms," said Kenneth L. Kusmer, a Temple University history professor. "If they had slave plantations, the feeling was this would be competition for labor, which people could not do if they didn't have slaves. It would detrimental to them economically."

Thus came the slogan for the convention in Philadelphia: "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men."

Some 600 delegates traveled to Musical Fund Hall, then a grand musical auditorium that had hosted the likes of French General Marquis de Lafayette and writers Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Horace Greeley. The building, since converted into condominiums, still stands on East Locust Street.

With the Whigs fractured, opportunities were emerging for new factions to compete with the Democrats, who represented much of the South, but still held some Northern support.

The American Party, better known as the "Know Nothing Party" was gaining traction, fueled by an anti-immigration stance that called for Irish and German Catholics to undergo a 21-year waiting period to be naturalized.

"This party arose rapidly in the mid-1850s," Kusmer said. "It elected quite a number of congressmen from the north and the south and local government officials and a few governors. ... Basically, it was an anti-Catholicism party."

The Republicans also had had some success in state and off-year elections, prompting their decision to nominate a presidential candidate in 1856, Miller said. They met in Philadelphia for convenience, but also because Pennsylvania was considered a battleground state.

Source/The Heritage Center

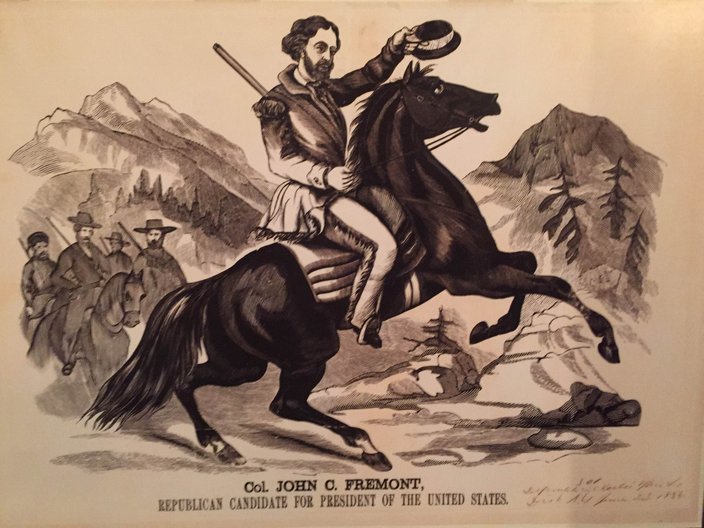

Source/The Heritage Center The Republican Party nominated John Fremont as its first presidential candidate at its 1856 National Convention in Philadelphia.

As their first presidential candidate, the Republicans nominated John Fremont, a Californian known as "The Pathfinder" for leading four expeditions into western territories. They selected William Dayton, of New Jersey, as their vice presidential nominee over Abraham Lincoln.

"I don't think he really wanted to do that," Kusmer said. "I think that he really wanted to be president. ... Prior to (Richard) Nixon it was not automatic, at all, that the person who had been vice president would then become the next presidential candidate."

The Democrats, of course, held onto the presidency with Pennsylvanian James Buchanan gaining 45 percent of the popular vote. Fremont received 33 percent while the former President Millard Fillmore, of the American Party, received 22 percent. And the United States continued its spiral toward civil war.

Despite the loss, the Republicans realized they could win the presidency in 1860 without winning any Southern states - if they could win Pennsylvania and either Indiana or Illinois, Miller said.

"The fact that they emerge as the opposition party speaks volumes," Miller said.

That, in part, set the stage for Lincoln's successful run four years later. Sensing an opportunity to gain the presidency, Republicans sought to nominate a more moderate candidate with a broader appeal. Lincoln, who had captured attention through various speeches, represented that.

"The Republican Party, like all parties, makes much about its origin," Miller said. "Everybody needs a creation story. They've got a creation story that goes back to 1854. ... In one sense, 1856 in Philadelphia is the real creation story."

Sweeping the Country: Political Conventions in Philadelphia is on display at The Heritage Center of the Union League of Philadelphia until February 2017. It features artifacts, images and stories from each of the 11 political conventions held in Philadelphia since 1848. For more information, click here.