June 10, 2016

Hayden Mitman /for PhillyVoice

Hayden Mitman /for PhillyVoice

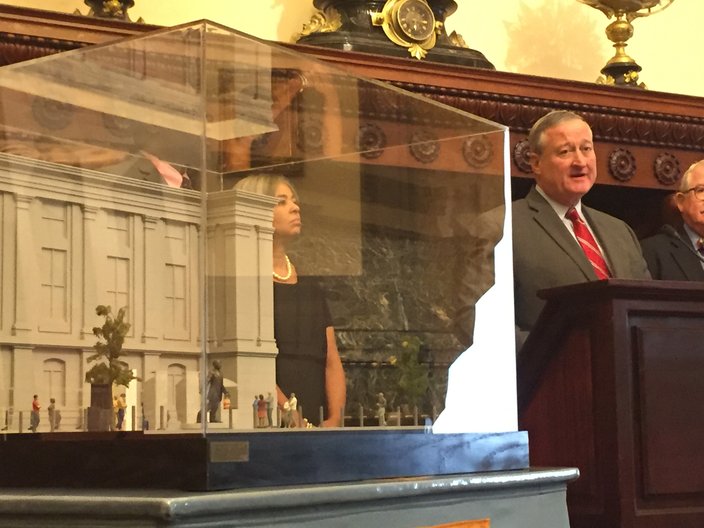

This model of the Octavius V. Catto memorial shows the statue, pillars and ballot box elements that will make up the $1.75 million project.

For nearly a decade, Mayor Jim Kenney has hoped to memorialize a 19th century African American civil rights leader from Philadelphia.

On Friday, the mayor was finally able to unveil the designs for a $1.5 million memorial that would honor Octavius V. Catto and celebrate the day that African Americans secured the right to vote.

"The only thing I can say is 'finally'," said Kenney during Friday's unveiling of the statue's design at City Hall.

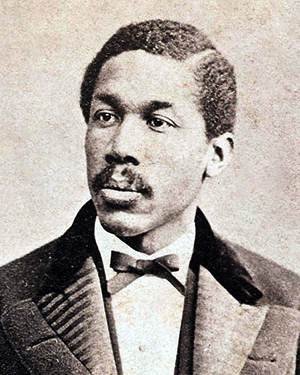

Octavius V. Catto

According to Kenney, he has been hoping to bring a statue of Catto to the city since at least 2003, after he learned the life story of the man who worked to desegregate Philadelphia's street cars – he succeeded which happened in 1867 – and fought for equal voting rights for African Americans.

The memorial - entitled "A Quest for Parity" - would be the first new statue added to City Hall's apron since 1923 and will cost about $1.5 million. The city has committed $500,000 toward the project, while the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund has raised matching funds, as well as additional funding. According to Carol Lawrence, co-chair of the memorial fund, an additional $250,000 will be raised and used to fund educational programs about Catto's life.

The fund is still working to raise the final $400,000, she said.

Expected to be erected and placed on City Hall's southwest curtain by the end of the year, the memorial will feature a 12-foot tall statue of Catto, five granite pillars – inscribed with a quote from Catto and designed to evoke the horse-drawn trollies Catto worked to desegregate – and a stainless steel ballot box, inscribed with the date of Oct. 10, 1871, the date that the 15th Amendment was ratified to give African Americans the right to vote.

"A lot of patience, a lot of effort has gone into this," said the mayor. "I can't wait to see it."

Mayor Jim Kenney speaks at the unveiling of the design of the memorial to civil rights leader, Octavius V. Catto, that is expected to be placed at City Hall by the end of the year.

So, who is this man getting a memorial?

During the day, Jim Straw, co-chair of the Catto Memorial Fund, called Catto a "forgotten hero."

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1839, Catto became a civil rights champion after he was kicked off of a horse-drawn trolley in Philadelphia, at that time segregated.

"In Philadelphia, at that time, you could be wearing a Civil War uniform and not have been able to get on that trolley car," said Kenney, who didn't know the story of Catto's life until he was in his 40s. "[Knowing this] you realize, this struggle isn't just a 1960s struggle. It's a struggle from the beginning of the country."

Related story: Online database of Philly abolitionist's diary to shed light on Underground Railroad

In his early 20s, Catto was already an active leader in the African American community. He was a member of the 4th Ward Black Political Club, the Union League Association, the Library Company and the Franklin Institute. He demanded that African Americans fight in the Civil War and helped get their regiments inducted into the war.

Catto was also a major in the Pennsylvania National Guard and played baseball as captain and second baseman for the Pythians, an African American baseball team. He was inducted into the Negro League Baseball Museum's Hall of Fame.

Catto also worked to promote the voting rights of African Americans – something that would get him killed at the age of 32. On Oct. 10, 1871 - the first day that African Americans could vote in America – Catto was reportedly headed to vote, while there were fights breaking out around the city between white and black voters. As Catto walked to his polling place, Catto was shot and killed near Ninth and South streets in South Philadelphia.

Artist Branly Cadet, of Oakland, California, said he visited the city and tried to walk in Catto's shoes to conjure up a memorial to the man. Cadet said he walked to 7th and Lombard Streets, where Catto attended the New Institute for Colored Youth – which became Cheyney University – as well as along Broad Street and down South Street, where Catto's home was near 8th and South streets.

"I wanted to familiarize myself with his life," said Cadet, who is also African American. "I walked where he walked... And, I was struck by how very different our experiences – mine and Catto's life – were."

Cadet said he designed the statue of Catto to be walking forward, his arms open, showing how Catto was moving toward the future and hoping to evoke familiar images of civil rights activists marching hand in hand together for a cause.

"The future he helped to create, and paid for with his life, is the future I get to live," said Cadet.

The memorial is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

Courtesy of the Urban Archives, Temple University/via Wikipedia

Courtesy of the Urban Archives, Temple University/via Wikipedia Hayden Mitman /for PhillyVoice

Hayden Mitman /for PhillyVoice