March 01, 2018

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

The Delaware River near the Benjamin Franklin Bridge between Race Street Pier, left, and Municipal Pier 9.

Facing an unprecedented water crisis, Cape Town, South Africa is restricting residents to a mere 13 gallons of water each day.

That's enough for a 90-second shower, two brushings of the teeth, one toilet flush, one cooked meal, a sinkful to wash dishes and a half-gallon of drinking water.

Residents who use more face fines.

The limitations have been enacted in hopes of pushing back the so-called "Day Zero," when Cape Town officials will shut off water taps across the city in an attempt to conserve the last of its diminishing water supply.

That day, initially set for April 12, has been bumped back several times to July 9, thanks to conservation efforts. At that point, it is expected that nearly 4 million residents will be forced to line up at collection points to receive daily rations.

It's a dreaded scenario that the port city – mired in a severe drought for three years – hopes to avoid by observing strict conservation efforts into the winter season, which historically brings greater amounts of rain.

But the crisis is aggravated by outdated water infrastructure, which has failed to keep pace with the picturesque city's population growth.

The crisis brings to mind the way another challenging water shortage – though far less severe – shaped the systems that now protect Philadelphia's water supply.

The Delaware River, shown here near the Walt Whitman Bridge, is the longest undammed river in the United States. The lower portions of the river are tidal and contain salt water, which advances upstream in times of drought.

Philadelphia is unlikely to wind up in a situation similar to Cape Town, in part because climate change is expected to make the region wetter – not more dry.

But lessons learned decades ago, when the Delaware River basin endured a severe drought, prompted infrastructure and management procedures that now protect the entire basin's water supply, which feeds both Philadelphia and New York City.

"We can get multi-year droughts, for sure," said Carol Collier, a former executive director at the Delaware River Basin Commission who now serves as a senior advisor for watershed management and policy at Drexel University. "But we've really got a good management system in place."

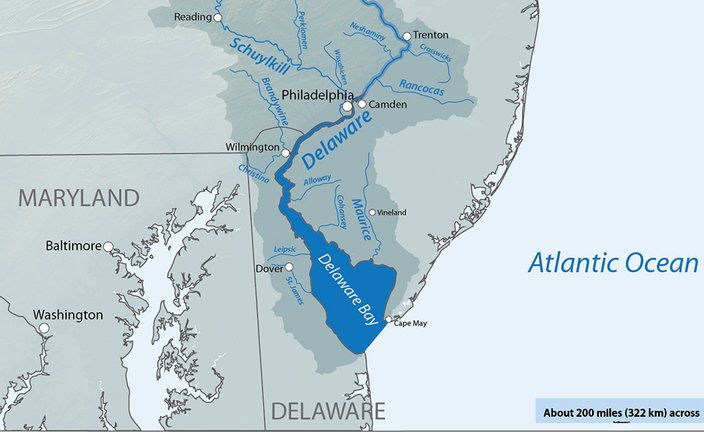

At 330 miles, the Delaware River is the longest undammed waterway in the United States east of the Mississippi, originating in upstate New York and emptying into the Delaware Bay.

Its basin – which counts the Schuylkill and Lehigh rivers among its 216 tributaries – provides a critical water supply for 15 million people living in four states. That's about 5 percent of the entire United States population.

"The size of the Delaware River watershed is moderate compared to the number of residents that rely on it for drinking water supply," said Lynn A. Mandarano, a Temple University professor who has studied water management practices within the basin.

"That's the issue that comes into play there. Do we have enough water for growing populations in that type of drought conditions?"

"If we didn't have the Delaware River Basin Commission, it would be an all-out fight for the governors and cities to make sure everybody was getting enough water." – Lynn A. Mandarano, Temple University professor

Every day, 944 million gallons are drawn from the basin for drinking water to power generation to industrial and agricultural uses, according to the basin commission, which manages the watershed.

But only 8 million of the people who depend on the Delaware River basin actually live within its boundaries. The others hail from New York City and portions of New Jersey, which both rely on basin diversions to supply significant portions of their populations with water.

Naturally, those diversions can create problems for downstream regions, like Philadelphia.

The Delaware River basin's worst drought on record – a multi-year shortage that lasted from 1961 through 1967 – put that on full display.

As the dry spell persisted, and reservoir levels dipped lower and lower, New York City unilaterally suspended legally-mandated reservoir releases designed to maintain a minimum freshwater flow down the Delaware River.

That mitigated the problem for New York, but it sparked a dire situation in Philadelphia, where officials worried about increasing salinity levels.

Because the lower portions of the Delaware River are tidal and contain saltwater, freshwater flows are needed to keep the salt line from advancing too far upstream, where a major Philadelphia water intake is located.

"The further upstream the salt front makes it, the more water has to be released to repel it," said Amy Shallcross, manager of water resource operations for the Delaware River Basin Commission.

With the region enduring a drought, and New York City suspending reservoir releases, the salt line advanced two miles north of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge.

That marked about 25 miles farther upstream than the salt line typically advances – and just eight miles downstream of Philly's Baxter Water Treatment Plant, located near the mouth of Pennypack Creek.

A water intake for South Jersey sits in nearby Delran, too.

"Your water treatment facilities on both sides of the river are not set up to treat for sodium," DRBC Communications Director Peter Eschbach said. "It's a taste criteria and not a human health criteria. They're not set up for it, but no one wants to drink salt water."

It put the Delaware River Basin Commission – an interstate-federal organization formed to manage water resources – to the test.

The Delaware River passes beneath a bridge spanning New Hope, Bucks County and Lambertville, New Jersey. The river basin, which includes 216 tributaries, provides water to 15 million people.

Today, the organization manages a wide array of watershed functions, including water quality protection, water supply allocation, conservation initiatives, drought management and flood loss reduction.

Across the country, there are similar bodies governing other watersheds. But it was a new concept when the long 1960s drought encompassed the Delaware River basin.

Enacted by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, the DRBC marked the first time the federal government and a group of states joined together to serve as equal partners as a river basin planning, development and regulatory agency.

"If we didn't have the Delaware River Basin Commission, it would be an all-out fight for the governors and cities to make sure everybody was getting enough water," Mandarano said. "Having this policy in place makes it better for the river commission to respond before it becomes an emergency."

"If you have a meter increase in sea level rise ... that saltwater is going to be pushed further upstream. If we do get drought conditions, it will be easier for that to be pushed into Philadelphia." – Carol Collier, former DRBC executive director

During the preceding decades, the Delaware River Basin had experienced an array of water supply shortages, apportionment disputes, water quality issues and devastating floods. The four basin states – New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware – often rushed to court to litigate water, particularly in regard to out-of-basin diversions to New York City.

In 1931, the Supreme Court ruled that New York City could export 440 million gallons per day from the basin, prompting the construction of two of the three Delaware River basin reservoirs that are owned and operated by New York City.

Two decades later, New York City petitioned the Supreme Court to increase its allocation. Though Pennsylvania and New Jersey fought the request, the court granted an incremental increase. But it also took steps to protect the water supply in the other states.

New Jersey was permitted to divert water along the Delaware and Raritan Canal, feeding water to Central Jersey.

The court also required that New York City conduct reservoir releases to maintain minimum flow rates at gauge stations in Trenton and Montague, New Jersey. That protected Philadelphia from an advancing salt line.

In theory, the plan worked. But the 1960s drought revealed that it was impossible to consistently meet flow requirements while also providing adequate water resources to New York City and New Jersey.

The Delaware River basin from its origins in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York to just north of Trenton.

Through the DRBC, the four basin states devised a drought management plan that reduces reservoir releases, lowers streamflow objectives and reduces water diversions to New York City and New Jersey.

The plan effectively preserves the water supply for New York City, while preventing the salt line to move too far upstream. The plan also established storage reservoirs.

Under the most severe conditions – when a drought emergency is called – the DRBC can request water releases from various basin reservoirs, or ask water to be stored in federal reservoirs.

"There really was a concerted effort in the basin to try to get it some resiliency to drought," Shallcross said. "We have these plans in place. Plus, the states ... can declare droughts and water restrictions. We usually work together with them."

That system kicked into place two years ago, when most of the Delaware River basin fell under moderate-to-severe drought conditions.

Three reservoirs in the upper basin released water, as did two others in the lower basin, to meet flow objectives.

Nevertheless, the salt line advanced 20 miles upstream of its normal November location, halting two miles south of the Schuylkill River's mouth, near the Philadelphia International Airport.

The salt line has not moved beyond that point since at least 1998.

"It's probably longer than that, but that's the most recent information that we have," Shallcross said.

As reservoir storage dropped, the DRBC deemed the entire basin under a drought watch, prompting reductions in out-of-basin diversions and flow objectives. Much-needed rainfall soon followed, preventing additional reservoir releases.

"We usually have this miracle storm sometime in the fall that will send a big pulse of water downstream and keep us at bay," Shallcross said. "Anytime you have rainfall, that helps us out and we don't have to make a release. But (the salt line) creeps back up if we don't get enough rain."

The Delaware River runs beneath the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. During the drought of record in the 1960s, the river's salt line advanced all the way to the bridge, threatening the city's water intake.

But while the system has prevented any major water crises within the Delaware River Basin, it remains threatened by climate change.

Philadelphia-area waters could rise 19 inches by 2050, according to Climate Central, a nonprofit organization of scientists and journalist that study the impacts of climate change. By 2100, local waters could be four feet higher.

Rising sea levels not only could put portions of Philadelphia underwater, but they threaten to push the salt line farther upstream.

Keeping the salt line within its normal range – near Wilmington – would require greater amounts of freshwater flowing downstream.

"If you have a meter increase in sea level rise ... that saltwater is going to be pushed further upstream," Collier said. "If we do get drought conditions, it will be easier for that to be pushed into Philadelphia."

That could place the city's drinking water at risk, and potential solutions are neither quick, nor inexpensive.

The Delaware River basin from Trenton to its terminus in the Delaware Bay estuary.

"There are things that can be done," Shallcross said. "They're usually very expensive. That is an issue that is going to be critical in the lower part of the basin."

To start, Philadelphia could relocate its Delaware River intake either upstream or on another tributary. The city has two intakes on the Schuylkill River, but derives about half of its water supply from the Delaware River intake.

Perhaps, the Delaware River intake would only draw water at low tide, when more freshwater flows downstream, experts suggested. Or the saltwater could be treated for both salinity and chloride, but that would require reverse osmosis, an expensive, energy-intensive process.

Reservoirs could be converted to multi-purpose. Or, in a very draconian move, a sea barrier could be constructed, as The Netherlands did two decades ago to prevent catastrophic flooding.

A Cape Town-like scenario is not likely in the cards for Philadelphia. But Collier said it should cause cities across the globe to consider threats to their water supplies.

"Climate change has such a different effect in different parts of the world," Collier said. "But I think Cape Town is really a warning gun."

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Tom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Tom Carroll/PhillyVoice Shannon1/via Wikipedia

Shannon1/via Wikipedia Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Shannon1/via Wikipedia

Shannon1/via Wikipedia