December 12, 2016

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

When Charles Grugan Jr. died of a heroin overdose in October 2011, the decision to donate his organs was made by his family: clockwise from top left, sisters Jennifer Grugan Whitehouse and Carolyn Grugan Noll, mother Eileen Grugan and father Charles Grugan. They posed for a photo at the Grugans' Wayne, Chester County, home where Charles had lived.

After her son Charles became addicted to heroin, Eileen Grugan was always fearful of getting that phone call, the one telling her that he had overdosed on the street or in a car somewhere.

“We were in so much pain. He wanted so bad to have a regular life and be happy, but the disease never leaves you alone,” she said. “Addiction is a long and lonely disease. When someone finds out that your son is an addict, they avoid you because they don’t know what to say.”

Charles was first introduced to Percocet at a party when he was a senior in high school. He wasn’t a drinker so he was looking for another way to get a buzz, his mom recalled.

“We talked to our kids about the dangers of drinking because alcohol addiction runs in our family, but we never thought to discuss pain pills,” said Grugan, who lives in Wayne, Chester County.

At first, he only took a pill or two once in a while, but when he went away to college, that’s when everything fell apart and he began using heroin, his mother said.

Charles’ tragic story is similar to the experiences of other heroin addicts. He spent a lot of time in and out of rehab and, in the worst throes of his addiction, ended up living on the streets.

“We had tried every possible therapy … tough love, cold turkey, methadone … He would be clean for a little while and then relapse again,” Eileen Grugan said. “But we never expected death to come even though we were preparing for it.”

“It is hard to believe that a life so tragic could end up doing so much good. Gift of Life gave us a chance to talk about addiction, to show that it can happen to any family, rich or poor. If I can save one life from addiction, then it is worth it to share his story.” – Eileen Grugan, who lost her son to a heroin overdose

On the Wednesday he overdosed, October 12, 2011, Charles was staying with his parents. He had just been released from jail a few days before. He had been clean for 14 months.

It was Eileen who found Charles unresponsive on the couch. The emergency response team that arrived after she called 911 was able to restart his heart, but he had already lost a lot of oxygen. They rushed him to Paoli Hospital, where they tried to save his life, but his brain had sustained too much damage.

Three days later, shortly after noon, Charles died.

“He was a great kid and despite addiction, a wonderful man. One thing addiction couldn’t take away was his goodness,” his mother said. “I remember when he got his license he was so excited to tell us that he selected to be an organ donor.”

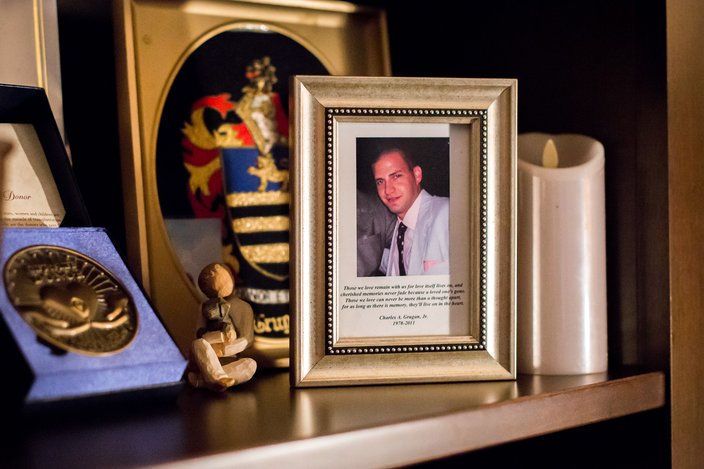

A portrait of Charles Grugan Jr. sits on a shelf in his parents' Chester County home.

Charles' family carried out his wishes, donating his organs – heart, liver and kidneys. His gift that day not only saved the lives of three strangers, it rescued his family, too.

“Our hearts had been broken for years as we watched Charles battle with his addiction and the Gift of Life transplant coordinator program came in and stopped the bleeding, giving us a way to heal,” Eileen Grugan said. “I don’t know how we could have been whole again without them.”

“It is hard to believe that a life so tragic could end up doing so much good," she added. "Gift of Life gave us a chance to talk about addiction, to show that it can happen to any family, rich or poor. If I can save one life from addiction, then it is worth it to share his story.

“We say that his organ donation is our silver lining. Gift of Life filled the hole in our hearts. He is never really gone as long as people are asking about him.”

“The victims of opioid drug overdose are often young and otherwise healthy, and many of them have organ donor designated on their driver’s license." – Robert M. Weinrieb, M.D., associate professor of psychiatry, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Giving the gift of life often helps families like the Grugans heal after the sudden loss of a loved one. With the rising opioid epidemic, the Gift of Life program in Philadelphia has seen an increase in organ donations from overdose victims as grieving families try to find a silver lining in death.

According to Robert M. Weinrieb, M.D., associate professor of psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, the number of people dying from an opioid drug overdose quadrupled between 2000 and 2014, and for many of the victims, their addiction started from pain medicine.

As many as 1 in 4 people on chronic pain medication become addicted, with no or insignificant improvement in pain levels. Higher and higher doses are needed for the same effect. Then, when they can no longer get prescriptions for the painkillers, they often turn to heroin, which is cheaper but with a shorter high, requiring several hits a day to keep withdrawal at bay.

“The victims of opioid drug overdose are often young and otherwise healthy, and many of them have organ donor designated on their driver’s license,” Weinrieb said.

Overdose victims are often good candidates for organ donation for two reasons: They die from a loss of oxygen to the brain, and they are usually otherwise healthy. Between 2006 and 2015, there was an almost four-fold increase in the number of organ donation from overdose victims in the United States, according to Howard M. Nathan, president and CEO of the Gift of Life donor program.

In the United States in 2006, 220 organ donors were drug overdose victims, a number that rose to 850 by 2015. In the Gift of Life region, which encompasses the eastern half of Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey and Delaware, the number of donors from overdose victims rose from 19 in 2006 to 81 in 2015. More than half of those organ donors were so designated on their driver's licenses. Sixty-one percent were male and 85 percent Caucasian. Ninety percent of these donors were between the ages of 16 and 45, with an average age of 32.

Eileen Grugan, mother of Charles Grugan Jr., holds a medal given to the family by the Gift of Life Foundation for donating his organs. The lives of three other men were saved.

Despite the tragic increase of death from opioid drug overdose, the need for organ donation still outpaces the number of organs available. According to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), an average of 21 people die each day while waiting for a transplant in the United States. Today, more than 119,000 men, women and children are waiting for a lifesaving organ transplant in this country, with more than 5,600 people waiting in Gift of Life’s region alone.

Nathan explained that about 1.5 million people die in U.S. hospitals every year, but only 1-2 percent can be donors. In our region, 38,000 people die in 131 hospitals every year, but only 800 (less than 2 percent) are potential donors. The average wait time for a kidney in Gift of Life’s region is four to six years.

The organ shortage isn’t due to a reluctance on the part of potential donors, according to Nathan, but because of the strict criteria that have to be met in order to be considered eligible. To qualify, the donor must be brain-dead on a respirator with good organ function, be free of infectious disease and match a recipient’s blood type.

Nucleic acid testing (NAT) is performed on the potential organ donor to rule out the risk of infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis C, which is especially crucial for donors considered high-risk like IV drug users. More effective than the older serology tests that look for antibodies in your blood, NAT identifies the actual viral genetic material, which reduces the window period in which an infection can be detected, Nathan said.

When the test comes back negative, but the potential donor had exhibited high-risk behavior, then the recipient must decide if they are willing to accept the organ knowing that the NAT testing may not be 100 percent accurate due to the three- to four-day window needed to detect the virus.

Nathan emphasized, though, that it is still important for individuals to register as organ and tissue donors. In Pennsylvania, there are 4.8 million people registered as donors, which is 46.8 percent of those who have a driver’s license or state ID. In the United States, 132 million people are registered – and only 52 percent of those with driver’s licenses or state IDs – showing the need for more people to register.

An urn containing the cremains of Charles Grugan Jr. sits on a shelf along with a teddy bear from his first Christmas, at his parents' Wayne home.

Because the need for organ donations continues to grow, the medical community is searching for safe ways to utilize more organs. The recent passing of the HIV Organ Policy Equity Act (the Hope Act), which allows HIV-positive individuals to donate to HIV-positive recipients, was a step in that direction.

Another was a recent study published in the American Journal of Transplantation that emphasized the need to educate potential recipients and their doctors on how the risk of disease transmission is actually lower than the risk of dying while waiting for an organ.

David S. Goldberg, M.D., MSCE, assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, an author of the study, and his colleagues found that despite the increase in the number of donors who were overdose victims, the mean organ yield for these donors was substantially lower than it was for other donor categories, partly because of concerns about infectious disease.

Goldberg is also involved in The THINKER trial at Penn, along with Peter Reese, M.D., MSCE, also an assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at Penn. The THINKER trial is investigating whether or not kidneys from hepatitis C-positive donors can be safely transplanted into patients who do not have the virus. Right now, only patients who are hepatitis C-positive can receive a positive organ, but the THINKER trial may change all that.

“One hundred thousand people are on the waiting list for kidney transplant,” Reese said. “There is a tremendous mismatch between organs needed and available donors. Treatment for hepatitis C has been totally revolutionized, and people are willing to take the risk. They are eager to get their lives back and to get off dialysis.”

This ongoing trial is currently enrolling patients between the ages of 40 and 65 who have a blood type of A, B or O. They must already be on dialysis and on the kidney transplant waitlist. In this pilot study, patients undergo transplant and then are treated with Zepatier, a hepatitis C therapy from Merck, to eradicate the virus.

Kiran Shelat, a Yardley, Bucks County, civil engineer who is participating in the trial, had his failing kidneys replaced on Aug. 4. When the hepatitis virus showed up two days later on tests, he immediately began a 12-week course of Zepatier. Within eight to 10 days, tests confirmed that the virus was gone.

Now, three months later, he is feeling great.

“My wish is that people under similar circumstances are encouraged by these stories,” he said.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice