April 17, 2018

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

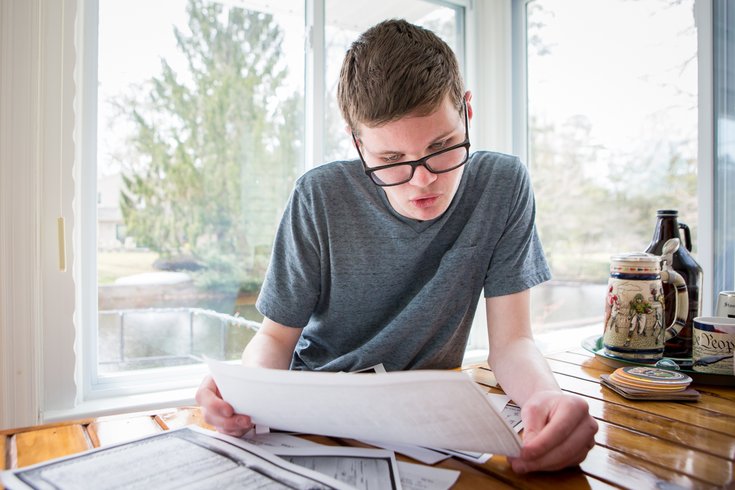

Eric Schubert, a junior at Shawnee High School, holds a copy of the 1910 United States census during an interview with PhillyVoice at his family's home in Medford Lakes, Burlington County.

What do you do when you've added some 15,000 people to your family tree and traced your mom's side back to the Middle Ages?

For genealogist Eric Schubert, it was time to start helping others research their ancestry, particularly adoptees curious about their biological roots.

With both Pennsylvania and New Jersey unsealing adoption records in recent months, that process has become much more manageable.

"It's been really fun and really humbling to help them out," Schubert said. "They've been looking for 20 years and within an hour or two of my time, I can open up entire new branches into their family tree."

Schubert, of Medford Lakes, Burlington County, is not a professional. In fact, he's still a junior at Shawnee High School.

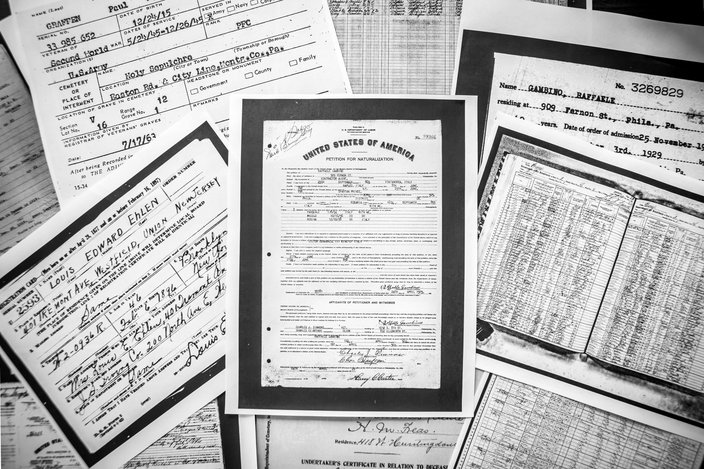

But he has helped some 500 people trace their lineages, including about two dozen adoptees. And he's got the census data, death certificates and naturalization records to prove it.

"I have notes everywhere," Schubert said. "My desk is insane. My parents call me the mad scientist. My friends call me the oldest teenager ever to live."

Schubert, who will turn 17 later this month, began researching his own family tree about seven years ago. His grandparents had all died and he wanted to learn more about their families.

Schubert thought he would finish the project in about a month. Years later, he was still going strong.

"It really just snowballs into 10 billion other things," Schubert said. "I think I have 15,000 people on my tree right now. It's just something that is really limitless and there's no designated end. So, you can just go on and on, which is what I've been doing."

Eventually, Schubert traced his ancestry back so far that it became very difficult to go much further. He's traced his mom's family all the way back to around the year 800.

"I'm not sure how accurate it is when you go back that far," Schubert said. "But it's really just cool to see how far you can go back and what you can do with it."

Now, he's helping others do that.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceA small collection of the documents, including a 'Petition for Naturalization,' that Schubert uses when tracing the genealogical history of individuals and families rests on his family's table. Many records have been digitized, whereas many he believes are still located in church basements throughout the world.

Two years ago, Schubert launched a website – ESGenealogy.com – to legitimize a word-of-mouth service already underway.

Schubert already had helped friends and neighbors trace their genealogies. But now, he turned his side project into one that earns him a little extra money – though he also does many genealogies pro bono.

"I was getting to the point where it was tough to find something to do in my tree," Schubert said. "I figured, well this is getting kind of stagnant. I should figure out something better to do."

With New Jersey opening up adoption records in January 2017 – and Pennsylvania following suit late last year – Schubert is particularly interested in helping adoptees research their biological families.

In some instances, his work has helped adoptees connect with biological family members.

One woman contacted her nephew after he drew up her family tree. Another was set to meet her half-brother last weekend. Yet another woman has plans to meet two half-sisters this summer.

Yet, not everyone is interested in actually meeting their biological relatives. Knowing this, Schubert said he simply presents adoptees with his findings, letting them pursue any connections.

One woman came to Schubert hoping to learn the identity of her birth mother. She only could provide Schubert with her mother's first name and age.

But when Schubert determined her mother's identity, the woman didn't want it.

"She was like, 'Never mind, I don't want it,'" Schubert said. "Some people just want to know if something can be found, in case they change their mind in the future. Because, obviously, it's a very emotional topic."

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice'I was getting to the point where it was tough to find something to do in my tree,' says Eric Shubert. 'I figured, well this is getting kind of stagnant. I should figure out something better to do.'

Ira Wolins, 56, of Philadelphia, asked Schubert to compile a family tree after he caught a television news feature on the student.

"It's just fascinating," Wolins said. "It's just good old nostalgia, just to see what you can find. Sometimes, you just want to say, 'Where did I come from?'"

Through Schubert's work, Wolins – whose family came from Russia – learned his father's grandmother had married five times. He also learned her father's name after Schubert found her death certificate.

Now, Wolins has tasked Schubert with determining another potential family connection.

"He does really good work," Wolins said. "He's really friendly and very responsive. ... It's almost like detective work, looking back into history. It's just interesting. It's enlightening."

Still, not all clients leave happy, Schubert said.

Many seek legitimization of family stories about relations to a famous person. Most of the time, there is little documentation to back up those claims.

"A lot of times when there is a family story that says, 'Oh, I'm related to so-and-so, nine times out of 10 – no," Schubert said. "Although it would have been cool because ... I'll spend days on it.

One family was convinced they had Native American ancestry. But Schubert could find no record of it.

Nor could he trace another woman to a Civil War general thought to be in her family tree. Others have sought to document distant relationships to former presidents, but Schubert has yet to confirm any of them.

"Some people are (like) whatever," Schubert said. "Some people are very disheartened and torn apart over it. It's really interesting to see."

Even when people question his findings, Schubert stands by his research. Yet, sometimes, genealogies can be hard to trace for a variety of reasons.

Immigrants' names were commonly changed upon entering the United States. Some names are incredibly common in certain locales. And information is not always complete or accurate.

For instance, the birth date on the death certificate of Schubert's paternal grandmother is incorrect.

"On her death certificate, it says she was born in 1909," Schubert said. "She was born in 1896. There's records of her – 1897, 1900s. She came over in 1902. For whatever reason, immigrants kind of shifted where they came over, when they were born."

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

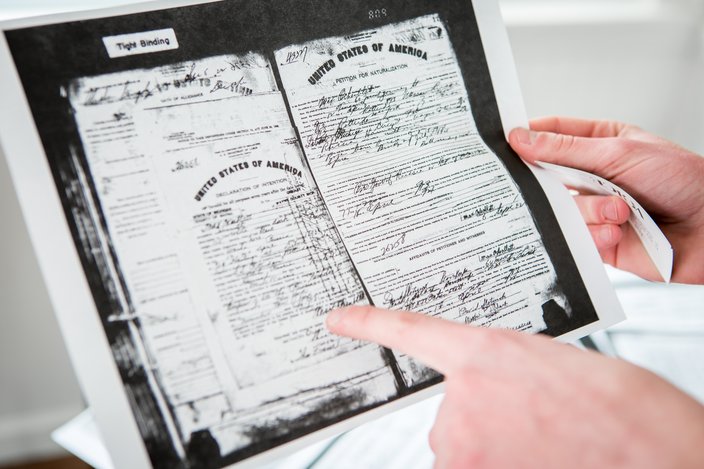

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceMany of the records that Schubert uses are handwritten. Sometimes, the illegibility can be a problem when analyzing the information.

Yet, Schubert enjoys working through those hurdles. He's learned to check various records to uncover missing information.

He has combed through all sorts of records – birth certificates, census data, naturalization papers, military records and death certificates – to track down an identity.

"It's pretty much hit or miss," Schubert said. "But I enjoy trying to figure out if I can crack it. It keeps me busy for a while until I go, 'All right, I don't think this guy is going to be easy to trace any time soon.'"

Schubert does not know where his genealogy efforts will take him – just like when he started tracking his own family.

He has not determined his college plans, but he is leaning toward studying business. Yet, he has no plans of abandoning genealogy any time soon.

It has been too rewarding.

"I'm busy all the time," Schubert said. "I love being busy, though. It's always fun knowing that I'm helping people 24/7 figure out these things that they had no clue about."