November 10, 2017

Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice

Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice

Church leaders at Trinity Church Oxford on Rising Sun Avenue in Northeast Philadelphia are seeking to lease land to Royal Farms because they do not have the money to maintain the parish house, above.

UPDATE, 6:20 p.m., Friday, Nov. 10, 2017:

Plans to demolish a Northeast Philadelphia parish house belonging to one of the country’s oldest churches to make way for a Royal Farms convenience store and gas station have been apparently stopped by the Philadelphia Historical Commission.

The commission voted late Friday to affix a historic designation on the parish house belonging to Trinity Church, Oxford in Lawndale after reviewing a proposal from the Preservation Alliance during a packed hearing.

All future building and demolition permits for the property will have to win the commission’s approval, effectively killing a lease deal that church officials had with Royal Farms. The convenience store operator had planned to build a new store across from a rival Wawa at Rising Sun and Longshore avenues.

Neighbors of the cash-strapped church, which, like many, was facing dwindling enrollment, had vehemently opposed the deal, saying the added traffic would disrupt the largely residential community.

“The community is elated,” said Heather Miller, who led neighborhood opposition to the Royal Farms plan. In the background, her 10-year-old daughter could be heard yelling “We won, we won.”

“What we would like to see now is a time for healing between the community and the church,” Miller said. “We would like to move forward together to find some use for the building that is beneficial for the church and the community.”

Calls to leaders of the church, which was first established in 1698, and to Royal Farms were not immediately returned.

– Frank Burgos

• • •

ORIGINAL STORY

It’s difficult to overstate the sanctity of the grounds surrounding Trinity Church Oxford, one of the oldest in the country, in Northeast Philadelphia.

The churchyard, crowded with tombstones, is the resting place for some of the city’s oldest families, including the brother of U.S. President James Buchanan, and an untold number of slaves in unmarked graves, their presence marked with a simple stone carved with the words ‘Free at Last.’ For parishioners and other Episcopalians in the city, Trinity Church, started in 1698, has been an institution, the mother church for about 12 others in the region.

The nearly six-acre church property spans from Rising Sun Avenue to Oxford Avenue, between Glenview Street and Longshore Avenue. For the neighbors in the Lawndale community, the grounds are where they grew up playing football and baseball in an open field, participated in Police Athletic League activities and dropped their own children off at a daycare run out of a parish house built during periods of enthusiastic expansion in 1928 and then later in 1963.

But now, there is an open, bitter battle over what to do with the land, as the church, facing dwindling enrollment and declining revenue, wants to move forward with a lease agreement with Royal Farms to demolish the parish house and nearby field to make way for a new convenience store and gas station, directly across from a rival Wawa at Rising Sun and Longshore avenues.

Church leaders say they are not interested in selling any part of the church property.

Neighbors, concerned over the added traffic, noise and gas pollution, have taken to the street with a bullhorn to protest nearly every Sunday after church services. And they have appealed to the Philadelphia Historical Commission to essentially stop the plan. On Friday, the commission is scheduled to consider a proposal by the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia to have the property declared a historic building.

Neither side seems ready to step down in a dilemma that some say other churches in the region may soon face themselves: a lot of property to care for and not enough money.

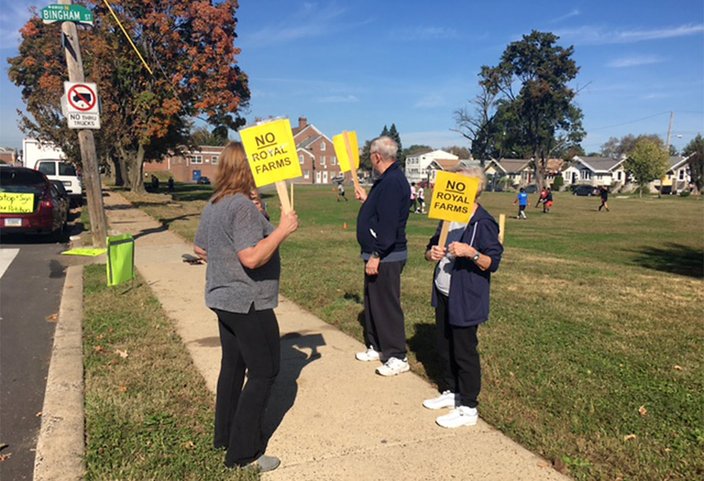

Heather Miller, who has been spearheading the opposition, was outside the church before a recent Sunday service, armed with a bullhorn and about a half dozen fellow protesters, who fear the pollution and traffic another gas station and convenience store would bring to the neighborhood.

“They want to come and demolish this beautiful building, which has been the community hub since the 1940s, longer than that,” Miller said. “On any given day the field will be filled with children. Why would we want to put our children right next to a 24-hour gas station?”

Calls to Royal Farms were not returned, but as far as church leaders and parishioners are concerned, the gas and convenience store company, famous for its fried chicken in the Baltimore and Delaware area, is their only hope.

A Lawndale congregation's plan to lease part of its property to Royal Farms is opposed by some neighbors who say the character of the neighborhood will change as a result.

Royal Farms operates five stores in Philadelphia and its northern and western suburbs, with more coming.

The chain hasn't been shy about locating near existing Wawa locations. Along MacDade Boulevard in Glenolden, Delaware County, Royal Farms built a new store less than 1,300 feet down the road from a Wawa store. Along Aramingo Avenue in Frankford, the competitors do business less than a half-mile away.

"If the whole block is sold, [the neighbors are] going get something up there and maybe something worse than Royal Farms.” – Jason McConomy, parishioner

But if built, the Royal Farms site on the church property would be the closest by far – less than 100 feet catty-corner across Rising Sun Avenue from its rival. If the plan advances, it would probably take 18 to 24 months for the store to open for business.

“This is a humongous piece of property that unfortunately takes a lot to maintain. We own this whole block” said Jason McConomy, a parishioner since 1969, after coming out of a church service. “We’re trying to preserve this area, this church. Royal Farms were the only ones interested in this opportunity.

“What the neighbors fail to realize is the Rising Sun area is a business district,” he said. “They want this maintained the way it is, want us to pay for it, but don’t give us any opportunity to get the resources to pay for it. They’re missing the big picture. Without Royal Farms and their income we can’t maintain this church and then the whole block will be sold. If the whole block is sold, they’re going get something up there and maybe something worse than Royal Farms.”

Residents hold signs at Longshore Avenue and Bingham Street to protest the plans by the congregation at Trinity Church Oxford to lease ground for a new Royal Farms convenience store. The parish house is seen at rear.

For Susan Feltwell, a 35-year resident who planted a sign on her front lawn declaring “No Royal Farms,” the dispute is over maintaining the peaceful characteristics of the neighborhood. “Traffic, trash, air quality,” she said, listing her reasons for protesting outside the church. She claims the church never told neighbors about its financial problems.

Lorie Henry, rector’s warden for Trinity Church Oxford, said keeping the aging parish house open was ultimately to the “detriment of the church and the graveyard, which is the truly historic part of this property.”

Parish leaders went to the Police Athletic League and others “to see if they would take over the building,” she said. There wasn’t enough interest. When the church announced it was entering into a lease agreement with Royal Farms, neighborhood protesters mobilized and have been outside the church every Sunday since July 16.

Both sides have stepped up public relation efforts to prevail in the dispute.

In hopes of winning over the community, Henry sent a letter to area residents two weeks ago asking for their input on what to do with land that would not be taken up by Royal Farms, if construction is finally approved with a zoning change. Among the options: construction of a playground, community garden or dog park. She also made clear in the letter the consequences if the Royal Farms deal fell apart: “We don’t want to close the church and fence off the area, but that’s what we’d have to do for liability purposes if this deal doesn’t go through.”

The church graveyard, which would not be affected by the development plan, is the resting place for some of the city’s oldest families, including the brother of U.S. President James Buchanan, and a number of slaves in unmarked graves.

“We’re encouraging people to just throw it into the trash,” said Miller of the letter. “It’s not an open dialogue of communication. They want the golden ticket [that Royal Farms] would bring in. We don’t believe they would follow through with it.”

Residents aim to erect a roadblock by having the parish building declared a historic landmark, which would require any construction plan to be approved by the Historical Commission. After meeting with neighborhood residents and inspecting the property, the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia submitted a proposal to the commission to preserve the Colonial Revival brick building, which features an auditorium, gymnasium and classrooms. The Alliance argues the parish house “exemplifies the cultural, political, economic, social, or historic heritage of the community.”

“We wouldn’t submit (a proposal) if we didn’t think there was historic significance to the building,” said Patrick Grossi, advocacy director for the Alliance, adding that Northeast Philadelphia has largely been “neglected” in the efforts to preserve historic buildings.

But he sympathizes with the church’s dilemma.

“They have a lot of land they are responsible for,” he said, which is typical for older churches who “tend to be the ones with the larger parcels of land. The buildings become the last source of revenue they have. We’re seeing that tension all over the city.”

He hopes that with some creativity, church leaders will find another use for the site.

Until then, Miller vows the protests will continue.

PhillyVoice graphic/Credit: Google Maps

PhillyVoice graphic/Credit: Google Maps Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice

Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice

Frank Burgos/For PhillyVoice