June 14, 2016

Credit/Will Drinker

Credit/Will Drinker

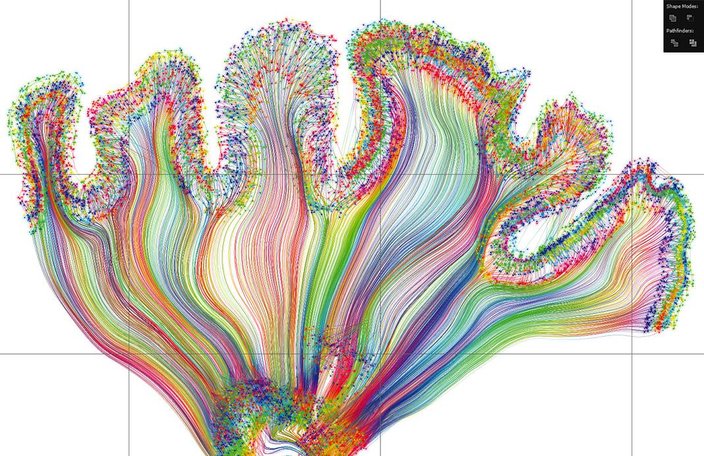

"Self Reflected," by local artist Greg Dunn in collaboration with University of Pennsylvania physicist Brian Edwards, is likely the most complex and detailed artistic depiction of the brain in the world. It stands 8 feet tall and 12 feet wide. This scene depicts the visual cortex plate.

The newest art addition to the Franklin Institute at first appears as a giant image of the brain etched onto a shimmering gold panel — simple yet beautiful, with the organ's squiggly silhouette instantly recognizable from afar.

But as you step closer to the artwork, the ornate intricacy of the piece reveals itself in breathtaking fashion. Dense spiderwebs of neurons huddle together to form the gray matter of the brain, while swaths of axons branch outward in all directions to illustrate the complex system of white matter connections. They bundle together at the base of the brain as hundreds of strands that collectively represent the brain stem.

The piece, created by local artist Greg Dunn in collaboration with University of Pennsylvania physicist Brian Edwards, is likely the most complex and detailed artistic depiction of the brain in the world. Not only does it depict half a million individual neurons to comprise a highly accurate slice of the human brain, the artwork also has a dynamic component to mimic the flickering of brain activity.

“We wanted to give the world a piece of art that is nuanced, detailed, and designed to pay reverence to the most phenomenal object in the universe that we all possess,” said Dunn. “The circuitry of the brain will be animated through reflected light to depict what is happening in the viewer's brain as they are looking at the piece — that's why the piece is called 'Self Reflected.' ”

"Self Reflected" stands a whopping 8 feet tall and stretches 12 feet wide, making it by far the largest and most complex piece worked on by the pair. The Franklin Institute will celebrate its new addition to “Your Brain,” the museum's largest permanent exhibition on neuroscience, with a public unveiling and introductory lecture by Dunn on Saturday, June 25 at 3 p.m.

“We throw out numbers in our exhibit like there are 86 billion neurons in the brain, but it's hard to wrap your head around that,” said Jayatri Das, chief bioscientist at the Franklin Institute and lead developer of “Your Brain.” “Greg's work will help people realize what that complexity looks like, where you can visualize the neurons and signaling. That will bring home the power of the brain in a way that really complements what our exhibit can do.”

This image of data, depicting the corticothalmic sheet, was used to create the final, finished microetching.

To create the artwork, Dunn and Edwards used a technique they invented called reflective microetching that uses sheets of gold engraved on a microscopic scale to allows flat surfaces to be seen as three-dimensional animated images. Tiny ridges applied by photolithography – the same method used to print circuit boards for the microelectronics that go in devices like cell phones and computers – precisely control how the gold in different areas of the piece reflect light to the viewer's eye.

Despite being categorized as artwork, a huge amount of science and engineering has gone into the creation of Self Reflected, which consists of 25 microetched panels carefully assembled as a unified piece. Previously, Dunn and Edwards had only worked on single-panel microetchings, and the scale of making something so much larger that also had to be mosaicked presented countless unforeseen problems during production.

Neurons were drawn individually using a blown-ink method to create the random, sprawling branches characteristic of the cells.

“The physics behind the microetching of such a large work had us between a rock and a hard place more than we've ever been,” said Dunn. “This is an engineering project at this point – there's no art going on, it's all quality control and analysis – which is still cool because we're scientists, and we enjoy doing this stuff.”

For instance, they found out the hard way that photolithography conditions had to be identical when making all the panels. If, say, one plate came out with a darker finish than the one next to it, the eye would notice the difference in contrast right away. At one point, all 25 plates had to be completely remade because the topography of their etchings looked visually incorrect.

Despite the hiccups, the entire project from conception to completion took a mere two years and received funding throughout from the National Science Foundation. According to the original proposal, Self Reflected will remain installed at the museum for at least 15 years.

“The real foundation point of the piece is to change the way that the average person thinks about the brain, and that's why we really invented this technique and are presenting the information in this way,” Dunn said. “People know what a neuron looks like and what the macroscopic walnut-shaped brain looks like – but our piece combines the two views.”

Self Reflected depicts a slice of the human brain in profile – known as a sagittal view in anatomical terms – based off of actual magnetic resonance images. The artists used structural images of the organ's folds, tissue types, and overall shape, as well as diffusion spectrum images that map white matter tracts which connect different regions of the brain. Neurons were drawn individually using a blown-ink method to create the random, sprawling branches characteristic of the cells. Dunn and Edwards scanned the neuronal outlines into a computer to create the grey matter and hand-drew fibers for the white matter. Finally, they use photolithography to create the microetchings and coat each panel with gold leaf.

Dunn, who received his Ph.D. in neuroscience from the University of Pennsylvania, is still relatively new to the art world and has been working as a professional artist for only five years. He was originally inspired by the chaotic, natural beauty of neurons as viewed through the microscope during his graduate studies, as well as East Asian scroll and screen ink paintings. His unique blend of rigorous science and emotion-evoking art quickly garnered attention, particularly from researchers and institutions.

“I would argue that neuroscience and the brain are really the unexplored frontier of the 21st century and important not just for understanding how we function as human beings, but also so we can learn more about how brain disorders work,” said Das. “This exhibit is an opportunity for the public to explore that understanding for themselves.”

Credit/Greg Dunn and Brian Edwards

Credit/Greg Dunn and Brian Edwards