December 20, 2016

A new study from Drexel University says black men are nearly three times more likely to die from police force than white men, and Hispanic men are almost two times more likely to die at the hands of officers.

The study's author says his findings contradict a July study that found severe racial discrepancies in how – and against whom – police use force, but not in the number of fatal encounters resulting from that force.

Dr. James Buehler, a clinical professor at Drexel’s Dornsife School of Public Health, looked at data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 2010 to 2014 and found 2,285 deaths attributed to law enforcement action during that time period.

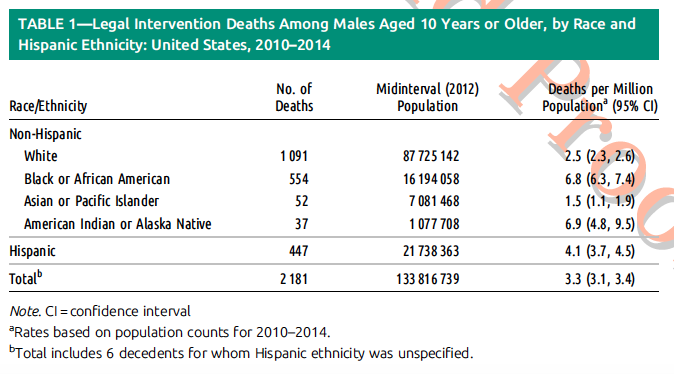

A whopping 96 percent of those deaths at the hands of law enforcement — by firearms, blunt force, explosions and other means — were of males ages 10 or older, Buehler found. And among that group, non-Hispanic white men accounted for 1,091 of the fatalities; black men accounted for 554 deaths; and Hispanic men accounted for 447 deaths.

But when those fatalities were compared to the racial composition of the total population, the statistics showed black and Hispanic men were much more likely to die from police force than white men.

Buehler compared the number of fatalities to the 2012 population of black, white and Hispanic men. White men died at the hands of law enforcement at a rate of 2.5 per 1 million people. Black men died at a rate of 6.8 per 1 million, and Hispanic men at a rate of 4.1 per 1 million.

The results of a study from Drexel professor James Buehler on racial discrepancies in deaths from police force.

Buehler conducted his research in direct response to a study published this summer by Harvard economist Roland G. Fryer. Fryer's study concluded that when it came specifically to officer-involved shootings, there were "no racial differences in either the raw data or when contextual factors are taken into account."

At the time of its publication, Fryer called the study's findings the "most surprising result of my career."

Fryer did find that black men and women are treated differently by law enforcement, as they're more likely to be handcuffed, pushed to the ground or have a weapon pointed at them.

However, when it came to officer shootings, including non-fatal incidents, Fryer found no racial bias.

Buehler said in a release that Fryer failed to factor in the "whole sequence" of events that could lead to a legal intervention death, as he focused on situations where lethal force might actually be needed. Fryer's study accounted for situations such as police responding to an aggravated assault and using lethal force, the Drexel researcher found, but left out police encounters like routine traffic stops that might result in deaths.

Buehler used a population-level study, which looks at the largest potential sample size, while Fryer used a more narrow method to try and account for a number of contextual factors.

Fryer's study looked at 1,332 shootings from 2000 to 2015 in six select cities and four counties in Florida.

He found officers were more likely to fire their weapons without first being attacked when the suspect was white and that white and black civilians involved in police shootings were equally likely to be carrying a gun.

The study's results seemed to contradict some of the grievances aired by the Black Lives Matter movement, which formed largely in response to the deaths of black men at the hands of police — like Brandon Tate-Brown in Philadelphia — and perceived racial bias in policing.

Buehler said while Fryer's study may "have alleviated concerns for some," he hoped his findings would call attention to disparities in legal intervention deaths.

Drexel University /Source

Drexel University /Source