September 12, 2016

Handout Art/Paul Kahan

Handout Art/Paul Kahan

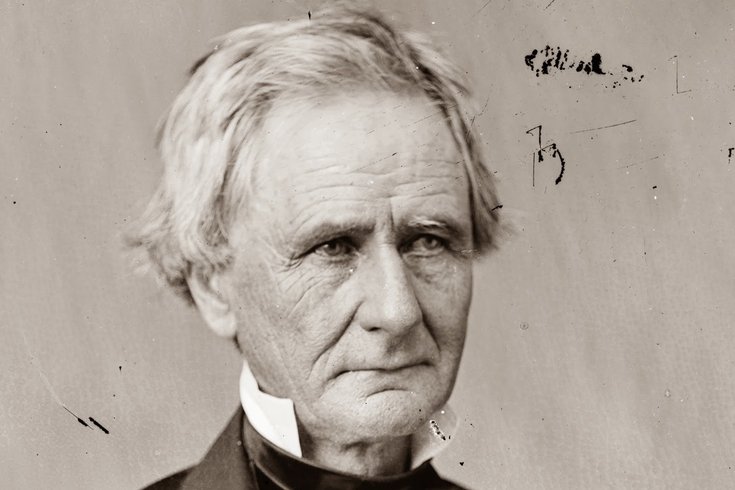

Simon Cameron, who served as secretary of war from March 1861 to January 1862. He was well-known as a party-machine Democrat in Pennsylvania.

A Bucks County native who grew up in Montgomery County, Paul Kahan is a Ph.D. in history from Temple University who's written three books in his career, including "Eastern State Penitentiary: A History" in 2008.

Kahan's latest book, "Amiable Scoundrel: Simon Cameron, Lincoln's Scandalous Secretary of War," released this summer — a deep-dive into the world of Cameron, who was not only Abraham Lincoln's secretary of war (until their arguments got him the boot), but once an editor of the Bucks County Messenger, a contender for the Republican presidential nomination and a well-known political boss of the Pennsylvania party machine.

Here, Kahan teases out the life of Cameron, what modern politician he's most comparable to and why he may get a bad rap for nothing.

What sparked your interest in Simon Cameron? There are lots of people you could study in politics, after all.

Well, I have always been interested in Pennsylvania’s history — it is a thread that runs through all of my books — but it was Doris Kearns Goodwin’s magisterial "Team of Rivals" that wanted to make me find out more about Cameron. The traditional depiction of Cameron is of a Machiavellian and corrupt politico who, as Secretary of War, proved himself totally inept. I was curious how and why such a clearly gifted politician was unable to translate those skills into success as Secretary of War. What I discovered was that there were only two biographies of Cameron: the standard one (Edwin S. Bradley’s "Simon Cameron, Lincoln’s Secretary of War: A Political Biography") and the first of what was supposed to be a two-volume bio (Lee Forbes Crippen’s "Simon Cameron: Antebellum Years"). Both were incredibly dated and incomplete and, with the 150th anniversary of the war looming, it seemed like a good time to reinterpret Cameron’s life and legacy.

'By creating a political machine that could reliably deliver Pennsylvania’s vote, Cameron made himself a player on the national stage,' says author Paul Kahan.

Cameron has a rich history in Pennsylvania — all over, even. Harrisburg, Lancaster, Bucks County, etc. What do you make of his commitment to the state? (And did he have any particular ties to Philadelphia?)

More than anything else, Cameron’s political success derived from his strong support in Pennsylvania. The Keystone State was incredibly important in 19th-century politics because Pennsylvania had the second-highest number of votes in the Electoral College. Put another way, nobody could win the White House without winning Pennsylvania, which put the commonwealth’s political leaders in the enviable position of playing kingmaker. Thus, by creating a political machine that could reliably deliver Pennsylvania’s vote, Cameron made himself a player on the national stage, serving three separate terms as senator — 1845 to 1849, 1857 to 1861 and 1867 to 1877.

That being said, Cameron’s commitment to the state’s interests was genuine; he once described himself as a Pennsylvanian first and a Democrat second. (Cameron was a Democrat before switching to the Republicans in the mid-1850s.) I think if there is a single thread that explains Cameron and his actions during his career, it is that he was passionately devoted to Pennsylvania’s interests, as he saw them. On one level, this was smart politics: as I noted before, being a national political figure in this period virtually required controlling your home state politically. On the other hand, however, there was a genuine desire to serve his constituents and to protect Pennsylvania’s interests.

Perhaps Cameron’s best-known connection to Philadelphia is the Union League. He was a leading figure in founding Union League clubs across the country, of which the one in Philadelphia is perhaps the best-known.

Handout Art/Paul Kahan

Handout Art/Paul KahanPaul Kahan, author of 'Amiable Scoundrel,' at a book signing.

Your claim is that he’s too interesting to be written off as just another corrupt politician. What do you mean by that?

There is a famous story about Cameron that, for many, says everything you need to know about him. Allegedly, Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, responding to a question about Cameron’s reputation for corruption posed by President Abraham Lincoln, said that Cameron 'Wouldn’t steal a red-hot stove.' Lincoln, whose relationship with Cameron was tense, repeated this line to his secretary of war, which enraged Pennsylvania. When Cameron encountered Stevens on the street several days later, he demanded Stevens retract the remark. Ever acerbic and clever, Stevens, in his next meeting with Lincoln, said, 'I believe the last time we spoke I said that Cameron would not steal a red-hot stove. I take that back.' Inevitably, when describing Cameron, historians and biographers repeat this story as proof of the Pennsylvanian’s corruption. It is a great story, and I tell it when I discuss the book. Unfortunately, it tends to obscure rather than clarify Cameron’s legacy.

That being said, the story tends to obscure more than it illuminates. Nineteenth-century American politics was driven by what was called the 'spoils system,' or the systematic distribution of patronage — government jobs and contracts — to politicians’ political supporters. In some sense, the entire purpose of winning elections was to get ever larger slices of the political pie that could, in turn, be used to strengthen and expand your political base so that you could ascend ever higher politically. Though this system had existed during the early years of the republic, it was institutionalized during the 1820s and became a basic element of the two-party system. Cameron became the most successful politico of his era — he was the only member of Lincoln’s cabinet to build an enduring state-level political machine — because he understood the spoils system and played the game better than anyone else.

Why the title ‘Amiable Scoundrel’? What can we glean from that?

If you boil Cameron down to his essence, 'Amiable Scoundrel' would be it. Here was a man who, over his long career, was repeatedly accused of being corrupt, yet even his enemies – men who hated him and his politics – universally conceded that he was pleasant and friendly to friend and foe alike. He was, in short, an amiable scoundrel.

'[Simon Cameron] understood the spoils system and played the game better than anyone else,' says author Paul Kahan.

What was his relationship with Lincoln like?

That’s a great question. Lincoln is the closest thing we have in this country to a secular saint. He is almost universally regarded as the greatest American president, so it is almost heretical to say a bad word about him. He is justly remembered for his patience and his forbearance. Yet, when it came to Cameron, Lincoln was uncharacteristically brusque and antagonistic. The President seems to have resented the fact that he owed his nomination and election as president, in great degree, to Cameron’s political influence and that the cost of those efforts was taking Cameron into the cabinet. Add to that the fact that Cameron consistently pressed Lincoln to go further than the president wanted to go on the issue of race — Cameron publicly advocated the enlistment of African-Americans in the army — and what you have is a very tense and difficult relationship, but one founded on a recognition that both needed the other to succeed politically. As a result, Cameron supported Lincoln in 1864 and was instrumental in delivering Pennsylvania’s electoral votes, which was a real achievement given that the President was running against Pennsylvania-native George McClellan.

What’s the biggest difference between politics today and politics in Cameron’s world?

We live in a post-civil service reform era. By the end of the 19th century, significant resistance to the spoils system had developed among both Republicans and Democrats, and they began institutionalizing reforms designed to curtail the amount of patronage that could be distributed. Moving forward, government jobs would be distributed on the basis of civil service testing rather than on the basis of political allegiance.

Personally, I think this is a good thing, but I also hasten to add that historians have often told this story as if the reformers are the 'good guys' and the spoilsmen were 'bad guys.' I think this is too simplistic; while civil service reform has been a 'good thing,' I think projecting that backward on men like Cameron prevents us from understanding mid-19th-century politics on its own terms.

If you had to relate Cameron to a living politician today, who would that be?

That’s a great question, but I have to be careful: I could get myself in real trouble here! I don’t know that Cameron is exactly like any contemporary politician, in large part because the political environment has changed so radically. That being said, in his longevity and ability to bounce back from defeat — as well as the sex scandal later in his career — I would say he is a bit like Bill Clinton. Clinton once described himself to Newt Gingrich as one of those inflatable punching clowns that we all had as kids. Clinton said something like, 'The harder you hit me, the faster I come back up.' This is the perfect metaphor for Cameron’s long career: whenever his political rivals thought they had delivered the knock-out blow, Cameron got back up and, in the end, he outlasted all of them.

What do you think are some admirable qualities Cameron demonstrated?

Cameron’s cardinal virtue throughout his life was loyalty and friendship, even for those with whom he disagreed politically. In addition, he had remarkably progressive ideas about race for the era, and he was extremely generous. In sum, he was a complete person, not just the cardboard caricature that his enemies — and historians — have depicted.