September 27, 2016

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

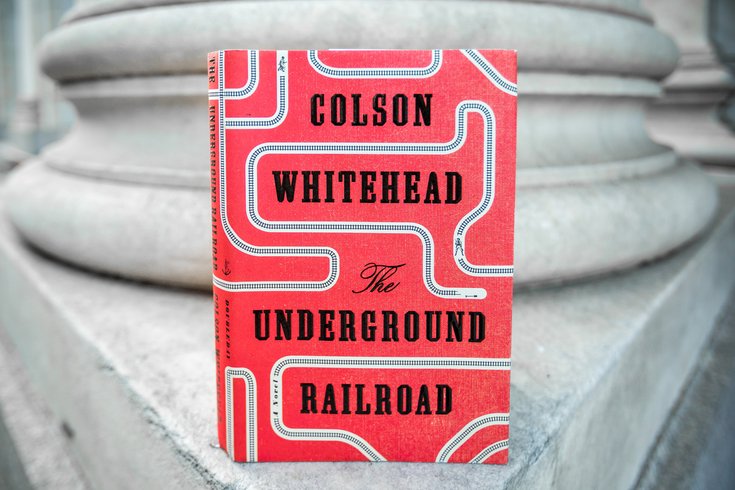

Oprah Winfrey selected "The Underground Railroad" for her book club, leading to its being published a month early.

Dystopias are usually the stuff of satire and sci-fi; our heroes struggle to survive under the thumb of some all-seeing power in a future that could one day happen! The lesson is about freedom, or individuality, or leaning against the momentum of a society that’s gone off the rails.

It’s easy to forget that dystopias can exist, that they have existed, that the United States was built on one.

“The Underground Railroad,” Colson Whitehead’s novel of anguish and escape in the Old South, has many of the hallmarks of those fascinating feel-bad classics we read in school. Our hero Cora — born into slavery on a brutal Georgia plantation where rape, forced labor and whippings are daily occurrences — has it as bad as or worse than D-503, Winston Smith and Offred. The oppression on the Randall farm at the hands of her legal "owner," his sons and their hired goon field hands is psychological, physical and total.

Abandoned when her mother fled the farm, Cora is also an outcast among her fellow slaves. She's relegated to the sleeping quarters reserved for the deranged and damaged.

Though Whitehead’s sparse and direct prose never lingers on the brutality of slave life, he doesn’t shy away from the facts of it. The lashes and other injustices are listed bluntly, and it churns the stomach. Because it’s happening to Cora and because it really happened.

Cora’s desperate escape from the Randall plantation seems inevitable, if only because that’s what’s got to happen in a book like this. But when you live in a dystopia surrounded by other dystopias, where do you run to?

Once Cora’s journey begins, “The Underground Railroad” takes on a structural resemblance to “Gulliver’s Travels” (and includes an overt nod to the Swift satire) as our hero encounters a series of societies built around premises that are horrible in new and unexpected ways.

There’s probably a name for this storytelling convention — “Watership Down” and “Star Trek” had similar skeletons — but I couldn’t find a term that fit comfortably. You know how Kirk and Picard were always running into civilizations run by computers or hippies, or that killed its old people? It’s like that, only the genre is more historically accurate horror than parable.

Cora’s desperation becomes your own as you follow her from one antebellum nightmare to another. Peace is all you want, for her and for you.

There’s a real actual train out there spiriting slaves to freedom right under the noses and fields of their oppressors, undermining their cruelty with glorious, industrial justice.

The central conceit of the novel — the thing that propels Cora on her journey; the thing you might’ve heard about even before Oprah rushed the novel to publication a month early; the thing you wished were true the first time you heard about the real Underground Railroad in history class — is that there’s a real actual train out there spiriting slaves to freedom right under the noses and fields of their oppressors, undermining their cruelty with glorious, industrial justice.

Whitehead doesn’t linger too long on the trains, either. The sci-fi nerd in you might want some technological specifics spelled out, but you’ll have to settle for the gorgeous and austere mystery of the situation. There’s a station at the bottom of a staircase. A train will emerge from the darkness and it will depart into darkness after picking up its passengers. It’s a means to an end, for the reader and for our hero.

That said, it’s a powerful moment when Cora first lays eyes on the massive locomotive by candlelight. For the first time, she was seeing something built by black hands that was not immediately taken away.

Read this book.

Tuesday, Sept. 23

Philadelphia Free Library

Parkway Central Branch

1901 Vine St.